September 8th, 2017—late into the dusk of a Caribbean twilight. An oppressive stench clung to the sultry wetness of the air; a stifling aroma of pulverized wood, organic rot, and something unidentifiable that’s reminiscent of decaying fish. Inky, pecan-brown puddles have pooled in the wrecked wasteland of sand and mud; they teem with jittering mosquito larvae, and ever-expanding colonies of flesh-eating bacteria.

Across Barbuda’s unrecognizable landscape, nightmares have become divorced from fiction. Debris is everywhere; and everywhere, there is debris. The entangled spoils of a war fought just days beforehand had formed a ruinous melding pot of fragmented buildings, ground-up tropical woodlands, and obliterated cars. Once-domesticated animals had now become lost and wild creatures, wandering aimlessly through the post-apocalyptic detritus, their fur mangled, and wet. The busy clamor of vehicular traffic, human colloquy, and Caribbean birdsong had lifted away like an untethered helium balloon… leaving behind a void of eerie, overwhelming silence.

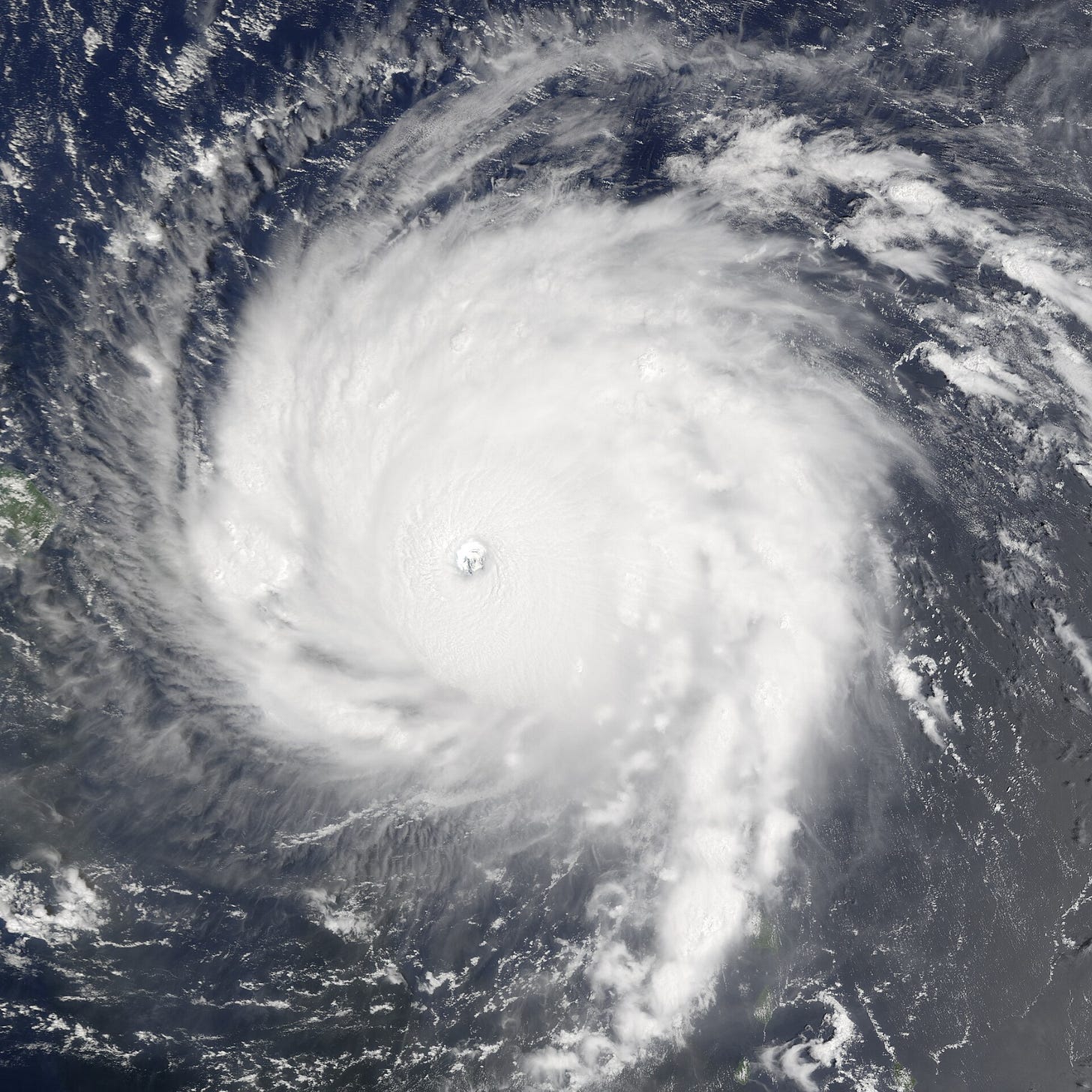

Just two days prior, Hurricane Irma had made landfall over Barbuda with maximum sustained winds of 180 mph… leaving the island horrifically decimated, and temporarily uninhabitable for the convents of modern human life. But Barbuda would merely be the first domino to tip from its tedious balance from the tightrope of nature’s equilibrium.

At the 5 am September 6th NHC Advisory—approximately 3 hours after the landfall in Barbuda—Hurricane Irma was already out on the hunt again. Being steered to the west-northwest by a subtropical ridge, and with nothing but favorable conditions ahead of her, she was lined up like a 180 mph bowling ball down the Caribbean bowling lane—and the Leeward Islands were the bowling pins. By the 5 am bulletin, Hurricane Warnings had gone up for a dizzying number of island nations lying to Irma’s west. These warned areas included:

SUMMARY OF WATCHES AND WARNINGS IN EFFECT:

A Hurricane Warning is in effect for…

- Antigua, Barbuda, Anguilla, Montserrat, St. Kitts, and Nevis

- Saba, St. Eustatius, and Sint Maarten

- Saint Martin and Saint Barthelemy

- British Virgin Islands

- U.S. Virgin Islands

- Puerto Rico, Vieques, and Culebra

- Dominican Republic from Cabo Engano to the northern border with

Haiti - Guadeloupe

- Southeastern Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands

- -Forecaster Beven

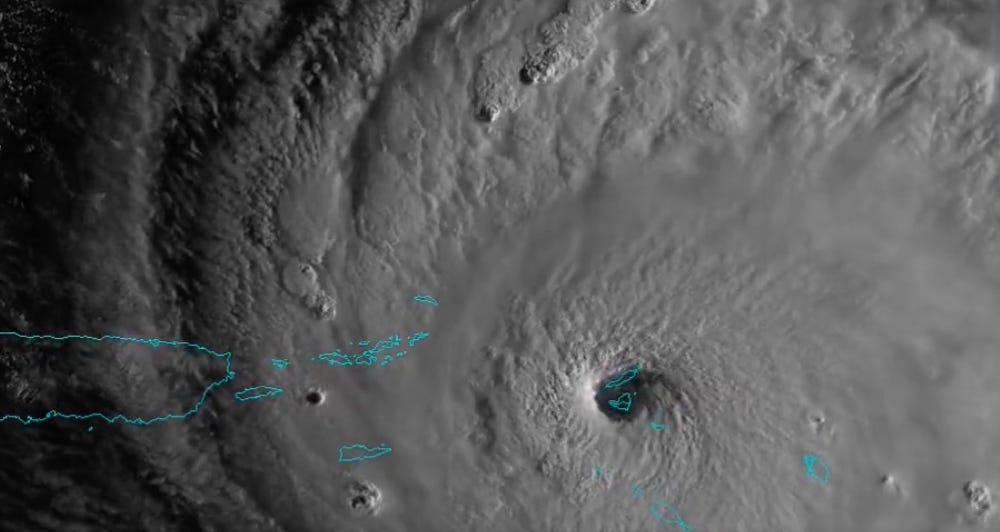

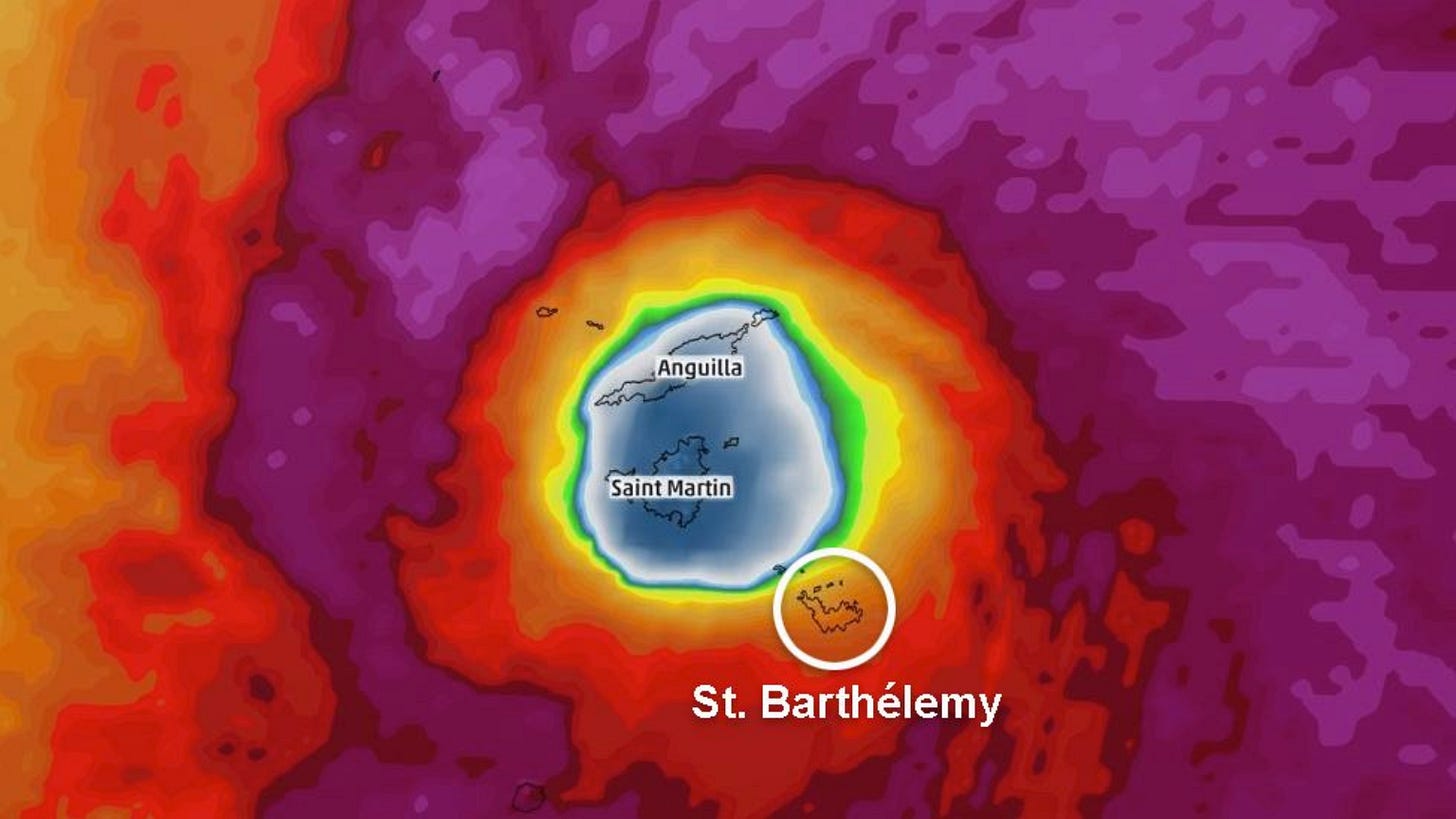

Of the above several dozen islands listed, the trio in the most immediate danger were the overseas European territories of St. Martin/Sint Maarten, St. Barthélemy, and Anguilla. It was here, where Irma’s hellacious core was forecast to churn through next:

BULLETIN

Hurricane Irma Advisory Number 29

NWS National Hurricane Center Miami FL AL112017

500 AM AST Wed Sep 06 2017

…EYE OF POTENTIALLY CATASTROPHIC CATEGORY 5 HURRICANE IRMA

MOVING AWAY FROM BARBUDA AND TOWARD ST. MARTIN…

SUMMARY OF 500 AM AST…0900 UTC…INFORMATION

LOCATION…17.9N 62.6W

ABOUT 35 MI…55 KM ESE OF ST. MARTIN

ABOUT 145 MI…235 KM E OF ST. CROIX

MAXIMUM SUSTAINED WINDS…185 MPH…295 KM/H

PRESENT MOVEMENT…WNW OR 285 DEGREES AT 16 MPH…26 KM/H

MINIMUM CENTRAL PRESSURE…914 MB…26.99 INCHES

-Forecaster Beven

At this time, there was still no word on the extent of the damage in Barbuda, nor the state of its citizens who’d just ridden out one of the most powerful Atlantic Hurricanes in recorded history—but this silence only added to the dark antipathy surrounding the fabric of Irma’s existence. Who else was going to face the same fate, that Barbuda did?

September 6th—The Domino Snowball.

During the twilight years of World War II, the United States employed a military strategy that they called “Island Hopping” against Imperial Japan, in the vast Pacific Theater of combat. Contingent to this strategy, U.S. forces methodically “hopped” from one Japanese-held island to the next, instigating fierce conflicts that laid countless square miles of tropical forests and local townships to ruin. From Tarawa to Guam, the Island Hopping (or “leapfrogging”) advance slowly ate away at Japan’s massive, oceanic empire, one small atoll at a time; and it would become the catalyst for some of World War II’s most notorious, and well-known conflicts, such as the Battles of Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.

On some level, this so-called “Island Hopping” is analogous to what Hurricane Irma was doing in the Atlantic Basin, in 2017. Much like those U.S. forces in WW2, Irma was not going to make a straight run for the heart of her adversary (in this case, the state of Florida in the continental U.S.). Instead, she would attack the individual islands of the Leeward Island and Greater Antilles first—systematically cutting through one, before hopping to the next, and the next thereafter. And if Barbuda was Irma’s Battle of Tarawa, then St. Barthélemy and Saint-Martin were her Battles of Peleliu, and Saipan.

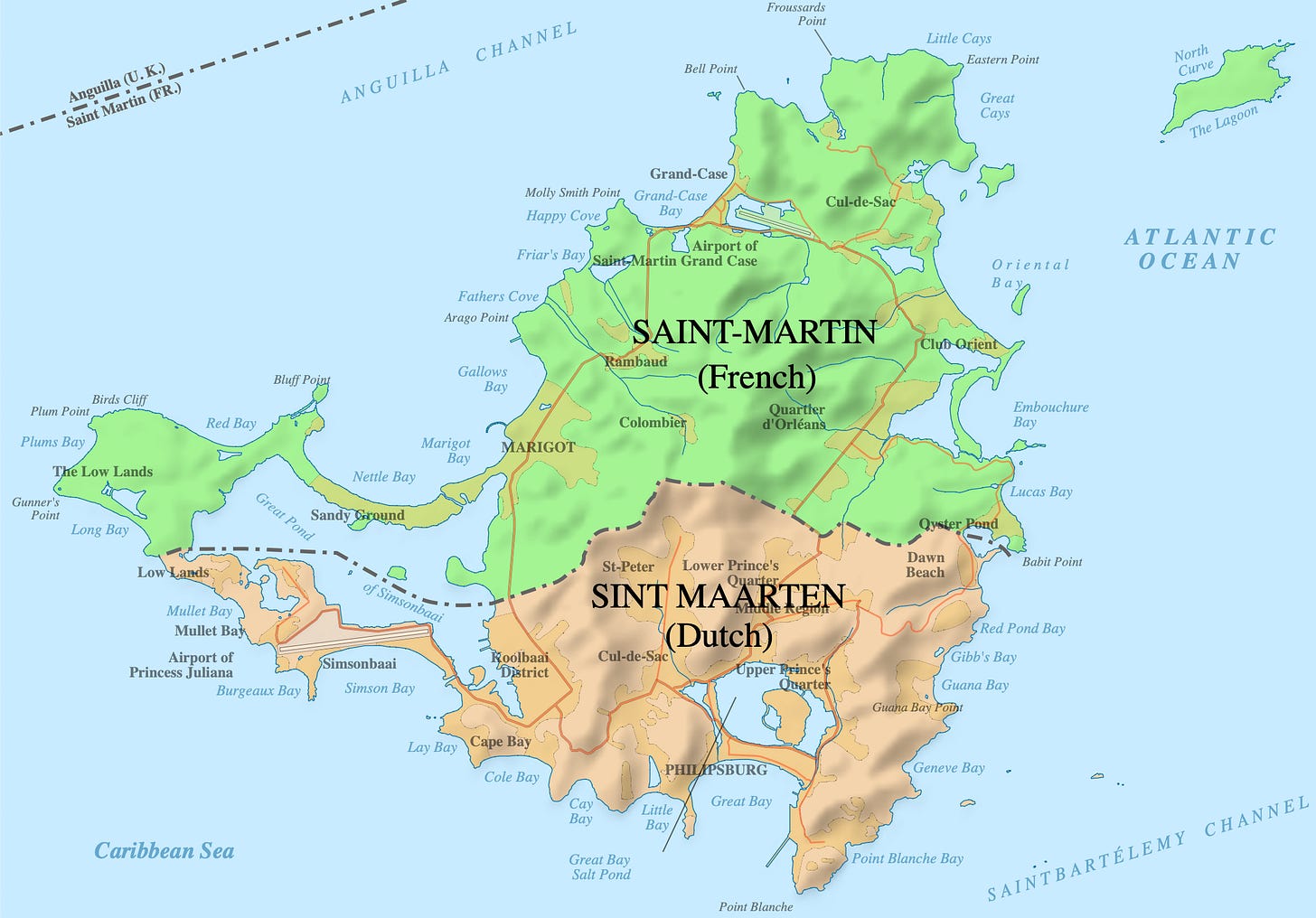

Before being conquered by colonial European powers in the 1600s, the island we now know today as Saint-Martin/Sint Maarten, once went by the name of Oualichi, which roughly translated to “the island of beautiful women”. But when it was discovered that rich salt reserves were buried in the island’s rocky soil, it was divided up in approximate halves by France and the Dutch Republic, by the signing of the Treaty of Concordia in 1648. Under this agreement, France would govern the northern half, while the Dutch controlled the south. Nowadays, it stands as a premiere vacation nook for wealthy tourists across the world.

In steep contrast to the flat marshlands and pristine ecosystems of its Leeward sister, Barbuda (which is located ~88 miles to the east-southeast), the island of St. Martin/Sint Maarten is mountainous, heavily developed, and densely inhabited, with a 2017 population of ~75,000 individuals (compared to just a few thousand for Barbuda). Surrounded by rocky bays, soft coral lagoons, and sandy inter-tidal zones, the island’s population centers encrust heavily vulnerable valleys and beaches in close proximity to the coast—creating a double-edged sword of mudslides and storm surge that is constantly threatening these resort-like settlements, anytime a tropical cyclone meanders by. Inland, the ground is layered with a much drier herbaceous biome than you’d expect for a tropical island, with dry grasses, and exotic cacti, among the plentiful menagerie of savanna plant species that can be found. This crispier climate is the result of the island’s hills creating rain shadows on their faces opposite of the Atlantic’s moist trade winds. Go nearer towards the beaches, and a more Caribbean flora of kapok trees, coconut palms, and bougainvilleas will return a semblance of sisterhood with the rest of the Leeward Islands.

Flanking St. Martin/Sint Maarten to the north and south, lie the islands of Anguilla and St. Barthélemy. The former, a sparsely populated, rural territory of the United Kingdom—and the latter, a minuscule French state that shines twice as brightly than its weight, as an opulent gem of the Caribbean Sea. Taken together, these three islands are embedded in the Atlantic’s deep tropics, and thus, share the common commiserations of being seasoned veterans of the plundering, Cape Verde Hurricanes that menace them on a near annual basis.

However, preceding the unseasonably cold, dark, and whistling sunrise of September 6th, 2017, these islands’ past cyclonic scars suddenly seemed to be of little defense against the extreme winds of Hurricane Irma, which were now rumbling just a few miles from their delicate, eggshell shores. By 5 am AST that night, those growling jaws clamped shut, and the onslaught began.

St. Barthélemy was the first of these luxurious, paradisiacal havens to slide down Irma’s abyssal throat. Under the cover of darkness, the Hurricane’s southwestern quadrant tore through the tiny island with unsettling ferocity. As was the case in Barbuda, St. Barthélemy’s lush, fertile topicality was all but stripped from its summertime soul. The native vegetation held up to Irma’s Cat 5 winds about as well as a sheet of paper caught between the steel blades of a scissor. Every major component of the island’s infrastructure suffered complete obliteration. Massive waves crashed upon the beaches, sweeping away beach clubs and hotels that were often frequented by Hollywood movie stars and millionaire moguls. Miscellaneous debris were transformed from innocent, inanimate objects, to deadly, bullet-like projectiles, in a matter of seconds. And, in the peninsular Capital City of Gustavia, floodwaters over 6 feet deep roared through the streets, tearing out the town’s guts, and spilling them into the raging sea.

Later analysis of an anemometer located on St. Barthélemy indicated that a 199 mph wind gust was, at one point, recorded inside Hurricane Irma’s eyewall, before the instrument permanently failed. By dawn’s light, it was as though the tiny, innocent island had been slayed by a tropical serial killer.

As the Sun continued to ascend above the eastern horizon on September 6th, Irma’s northwesterly movement was now taking her swirl of strongest winds into new territories. With the storm’s eye passing directly over St. Barthélemy—still blazing with a pressure gradient of 914 millibars—conditions on Saint-Martin/Sint Maarten (whom’d already been entrenched in the drenching downpours of Irma’s CDO for several hours), were quickly becoming wrathful.

While the morning sunlight shadowed the frothing bubbles of Irma’s rainbands, as well as the creamy swirl of the atrociously strong eyewall, winds on Saint-Martin were rapidly increasing. Power was lost by dawn’s arrival, and all communications with the outside world followed soon afterwards. Storm surge lunged forward into the coastal communities of Anse Marcel, Grand Case, Orient Beach, and Marigot, wiping out whole buildings like a ravenous dog cleaning out its bowl. Gales, still whirling at sustained speeds of 180 mph, flipped over cars and gutted hotel rooms with ease. Entire trees were toppled and uprooted. Exposed windows were shattered. Roofs, torn off like candy wrappers. And in Saint-Martin’s numerous marinas, flocks of white sailboats and small leisure yachts were smashed into each other, capsized, and crushed. This dock and marina damage was particularly severe in the Port City of Marigot, where violent waves were stirred into a devastating frenzy during the first half of Irma’s eyewall.

At the same time, on the southern side of the island, Sint Maarten was experiencing similarly catastrophic impacts. Tornado-like damage was inflicted to thousands of individual residences, leaving them virtually uninhabitable. The Princess Juliana International Airport—famous for its very low final approach course directly over a popular vacationing beach—was clobbered to pieces, with whole sections of the main terminal and boarding bridges snapped off and thrown haphazardly across the runway. The winds on Sint Maarten were so intense that, at one point, eyewitness accounts describe whole automobiles being lifted aloft “as if they were matches”.

Less than 5 miles to the north of Sint Maarten, Anguilla was simultaneously being rocked by Irma’s right-front quadrant—which is, traditionally, the most powerful quartern of a Hurricane’s eyewall. On this flat, low-lying island of limestone bedrock, the ramifications of Irma’s vivacious ferocity were much the same horror story as the neighboring islands to the south. Power lines, ripped from their poles in an electric flash; trees, deracinated from the saturated, sandy soil; homes, schools, hospitals, and public buildings, left windowless, and badly damaged. An anemometer at the Anguilla-Clayton J. Lloyd International Airport, elevated ~98 feet off the surface, measured 10-minute sustained winds of ~190 mph.

By 8 am in the morning on September 6th, the eye of Hurricane Irma was passing directly over Saint-Martin and Sint Maarten, thereby marking the storm’s 3rd landfall at Category 5 intensity (following Barbuda and St. Barthélemy). During this landfall, Irma’s central pressure had risen only slightly off her peak intensity, at a value of 918 millibars; while her winds continued to spin at a neck-breaking 180 mph.

Concurrent at the point when Saint-Martin was entrapped beneath the crystal-clear skies of Irma’s eye, St. Barthélemy was once again becoming consumed by the Hurricane’s eyewall—this time, in the southeastern quadrant. Saint-Martin and Anguilla would follow suit just minutes later. As was the case in Barbuda, the two sides of the Hurricane worked in tandem to strip the trio of islands to their bare, naked bones.

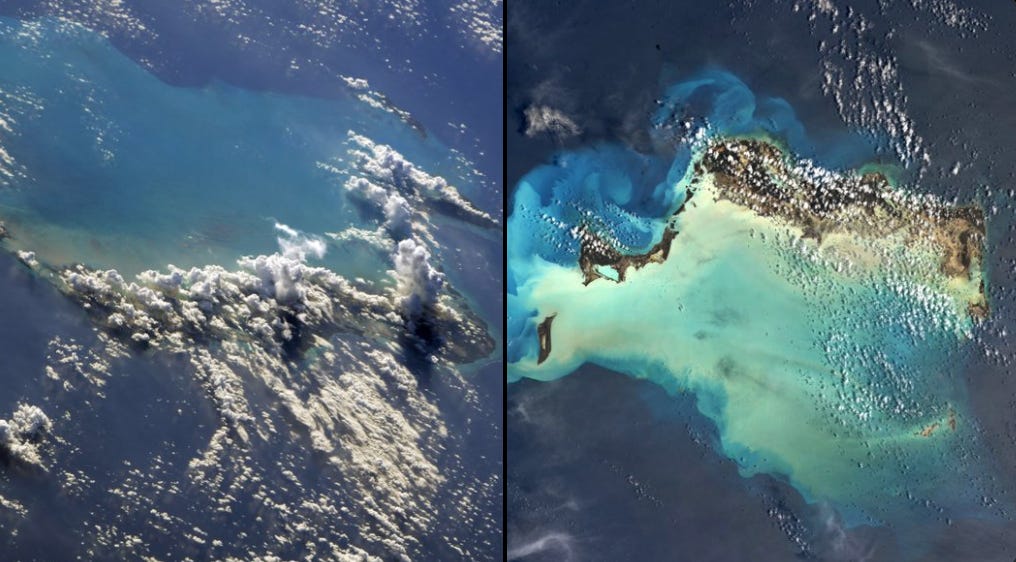

When Irma finally began to pull away to the northwest, these Crown Jewels of the Caribbean were left blemished, chipped, and for a time, practically gimcrack. Lands of tropical paradise, seductive beauty, and overwhelming tourism wealth, were reduced to brown, ugly wastelands.

The post-apocalyptic scenes were that of terrible sequels to Irma’s original landfall in Barbuda. For St. Martin, upwards of 95% of all buildings were severely damaged, with around 60% of them fully destroyed. On the other side of the border, in Sint Maarten, 70% of the total infrastructure was calculated to have been completely ruined.

The situation on St. Barthélemy and Anguilla was not much different, with the hills, the cities, and the marinas, razed to spoils. Over 9,000 miles and 73 years removed from the wartime carnage of an “Island Hopping” campaign, it was a carnal force of Nature, not Man, that was wreaking total destruction across these tiny islands.

The Virgin Islands.

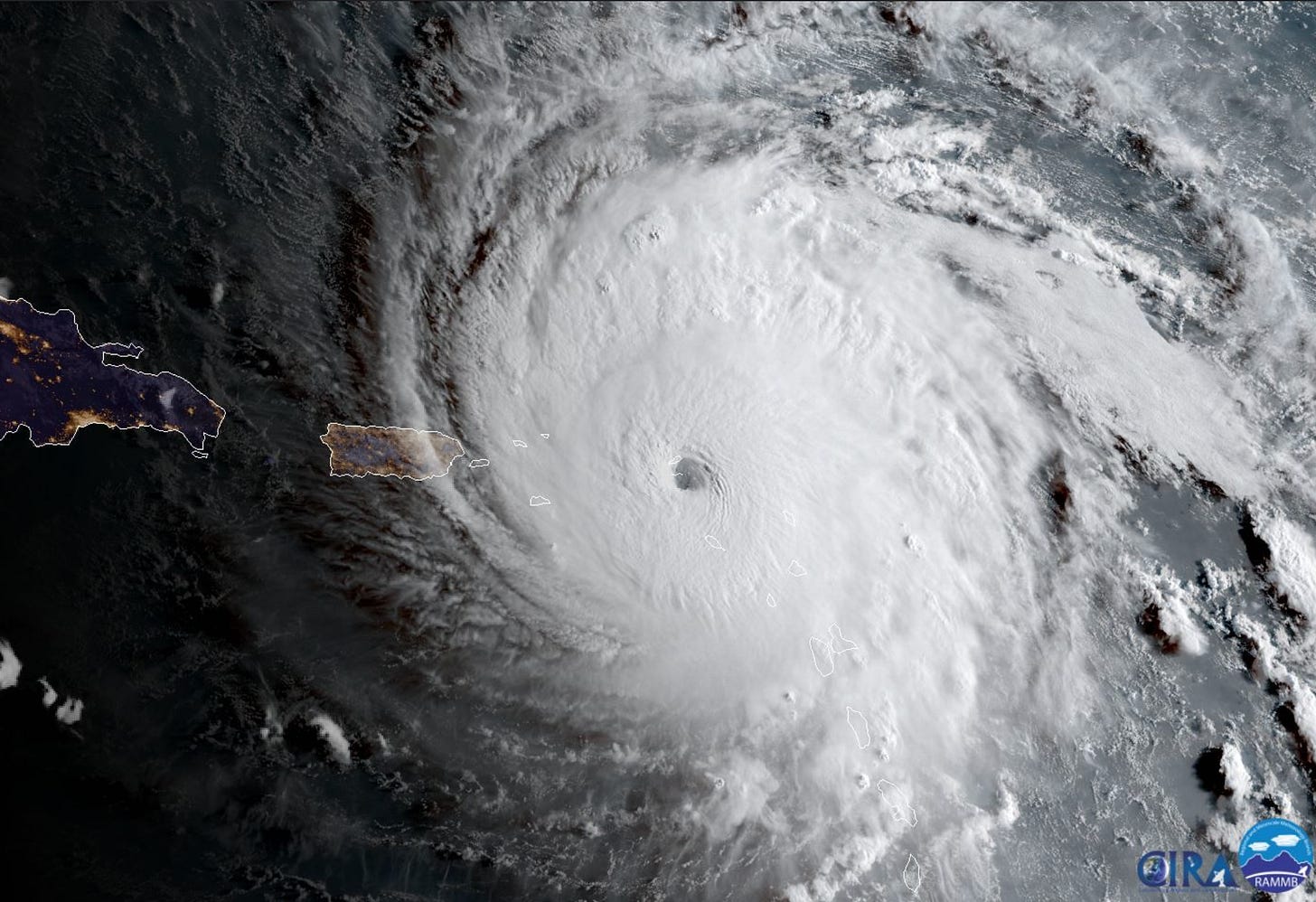

At the warming of the daylight on September 6th, Irma had already accumulated a body count of 2-3 landfalls in the Leeward Islands—all of which entailed the strongest sustained winds ever observed in an open Atlantic Hurricane. Yet, this voracious storm had not satisfied her predatory instincts for the day, and was already eyeing up her next quarrel: The British and U.S. Virgin Islands.

Come upon by the South American Ciboney people around 300 BC, named by Christopher Columbus in 1493, and being host as one of the most notorious Caribbean pirate hideouts throughout the 1500s, the British Virgin Islands are collectively represented by more than 60 tropical islands and islets, ranging in size from twelve miles long, to less than one. This picturesque archipelago was originally forged in the flames of intense volcanic activity many millennia ago, an origin that can be plainly seen by the island’s rugged, lumpy geography. The terrain is covered in moist forests, xeric scrublands, and Caribbean Resorts. Along with the adjacent U.S. Virgin Islands to the west, these lands are a beauty of flip-flop sands and gleaming cruise ship harbors, while demurely withholding the dark underbelly of being a primary axis of the North American narcotic drug trade.

By 11 am AST, Hurricane Irma—her lips, still messy from her latest meal just a handful of hours beforehand—was already closing in on the Virgin Islands Archipelago. It had been less than twelve hours since this immense and extremely powerful Hurricane had first embarked upon her grand feeding frenzy in the Caribbean, and in the same way that a shark can smell a single drop of blood in an Olympic-sized swimming pool, Irma seemed to have an acute ability to seek out every pinprick speck of land in the Atlantic’s vast oblivion—and subsequently devour it into her bowels.

As early as two days preceding this, on September the 4th, the British Virgin Islands (BVI) Department of Disaster Management had been originally predicting the storm to cut through their archipelago with sustained winds of 110 mph, which would’ve made the storm a high-end Category 2 Hurricane. So when Irma rapidly intensified the next day (September 5th), and far exceeded not just the Cat 2 ceiling, but the Category 5 threshold as well, government officials devolved into a panic. Without an adequate magnitude of preparations being organized, the British Virgin Islands were suddenly facing a Hurricane so powerful, she was triggering seismometers (instruments used to detect earthquakes) on nearby islands in the Lesser Antilles, as they detected the Earth-shaking fury of her 180 mph core wind speeds (some even speculate that the seismic readings may also have been due to the unimaginable number of trees that were being broken to the ground by the storm’s eyewall, at any one point in time).

With the center of Irma initially forecast to make a direct hit on the island of Anegada, which would bring an anticipated storm surge deeper than Anegada’s highest point above sea-level (25 feet), the BVI’s Government ordered a ferry to be sent to evacuate every resident from the island to other, less-vulnerable places in the BVI. Only some Anegada residents actually chose to leave on this ferry.

At around 4:30 am AST, September 6th—when Irma’s eyewall was cutting through St. Barthélemy, and imminently approaching Saint-Martin and Anguilla—the decision was made for all electricity across the BVI to be cut, as the lashing of tropical storm-force winds continued to increase. Then, at 5:39 am, a public alert message was sent out by the Dpt. of Disaster Management. As chronicled in the book, The Irma Diaries, this message read as follows:

“At 5:00 AM, the National Hurricane Centre has indicated that Hurricane Irma’s maximum sustained winds remain near 185 miles per hour (mph) with higher gusts. Irma is the most powerful Atlantic hurricane in recorded history and will be the strongest system to ever make landfall in the Caribbean. … Based on the latest forecasts, the approximate closest point of approach to Road Town from Hurricane Irma is 17 miles northeast.”

By 9:30 am, winds had increased further to Hurricane-force (74+ mph sustained), and the rain was descending sideways in a whipping deluge. Two hours later, at 11:30, the Dpt. of Disaster Management released another, and ultimately final, message to the citizens of the BVI, before all communications were lost:

“We are in for a direct hit, a direct hit on Road Town! Move, move to safe room immediately! Move please to safe room immediately! Immediately! Move please.”

Shortly thereafter, the eyewall crashed into the U.S. and British Virgin Islands, initiating Irma’s feeding process anew.

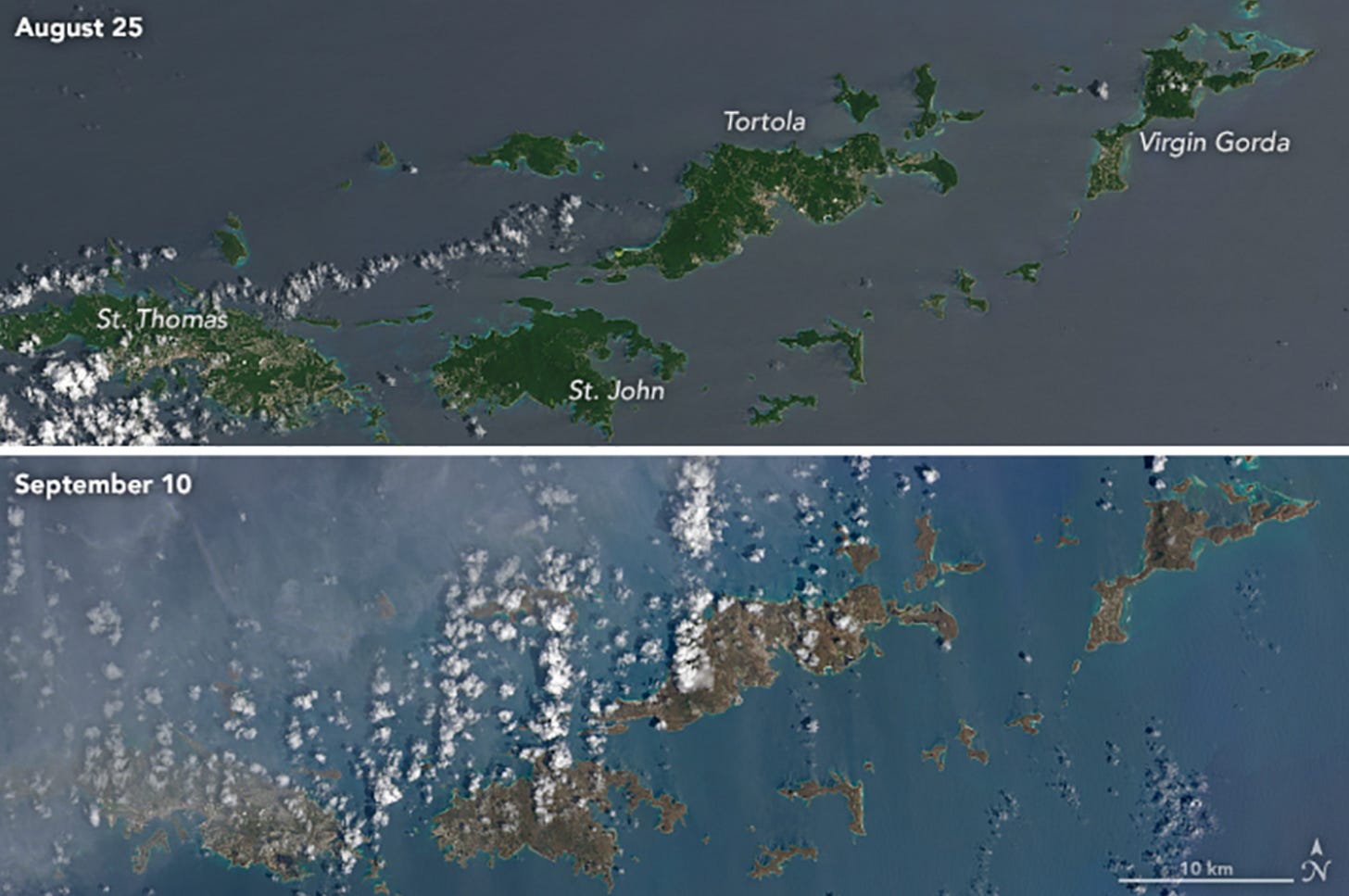

Like the detonation of a nuclear bomb built out of water vapor instead of plutonium, Irma sent a shockwave scorching across the more than 110 isles that make up the Virgin Islands Archipelago. Approaching her 12th consecutive hour of maintaining 180 mph gales, the storm pounded down at any and every acre of land she could, with unrelenting viciousness. Trees were once again ground down to husky shreds of their former selves… most, were even stripped of their bark. Roads were peeled up and washed out. The electricity infrastructure everywhere was totally destroyed. Food, water, and other basic services were severely compromised. Docks crumbled, and sheet metal was warped like tin foil. In the BVI, the island of Tortola would be recognized as having suffered the worst destruction, with United Kingdom Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson later saying that the decimation reminded him of the images of Hiroshima, Japan, after it was hit with the atomic bomb in 1945. Additionally, the mansion of British Business Magnate Richard Branson, was also destroyed.

Irma made her official landfall on the island of Virgin Gorda, BVI, at around 1 pm AST, September 6th, with winds of 180 mph, and a pressure of 920 millibars. In the aftermath of the storm, 85-90% of the buildings in the BVI endured virtually irreparable damage, with many homes near the beaches completely annihilated by Irma’s devastating storm surge. Among the buildings wholly destroyed were the offices of the Dpt. of Disaster Management themselves, in an eerie ode to just how final their last, dire emergency message to the people of the BVI truly was.

Contemporaneously, in the city of Road Town, power lines, chunks of roofs, and twisted metal were crammed into the narrow streets; and at the Balsam Ghut Prison just outside of the city, breaches in its perimeter security allowed several prisoners to escape through damaged sections of the outer fences (though all but two of them later returned to the prison voluntarily).

Meanwhile, on the U.S. side of the Virgin Islands, all airports and shipping ports were rendered inoperable. Stilted homes—spiraling up the faces of the islands’ knobby, igneous hills—were defenseless against the Hurricane’s ferocious winds (which were blowing even stronger at higher elevations). Whole floors of these houses were eviscerated to structural crumbs strewn down the sides of these hills. At the Charlotte Amalie hospital on Saint Thomas, patients from the top floors of the building had to be moved to lower stories, as rainwater poured in through holes that had been ripped open in the roof. Damage was likewise devastating on the other two major USVI islands of Saint John, and Saint Croix.

By the time Hurricane Irma had finished ruthlessly battering the Virgin Islands, she had achieved 3 direct landfalls (though St. Barthélemy, Anguilla, and the USVI all received the worst of the eyewall without the eye passing directly above their heads), as a historically strong Category 5 tempest, in just 11 hours. In doing so, she became just the second Hurricane in our recorded, meteorological history to make landfall in multiple nations at Cat 5 status (the first instance being Andrew in 1992, when he struck The Bahamas and South Florida). Moreover, as the first Cat 5-level storm to affect the Leeward Islands, Irma easily surpassed Hurricanes Donna (1960) and Luis (1995) as the costliest storm to impact these areas in modern history.

Tropical Trivia—Before Hurricane Irma (2017), which Atlantic Hurricane was considered the costliest storm to strike the U.S. Virgin Islands in the modern era?

A. Hurricane Hugo (1989)

B. Hurricane Marilyn (1995)

C. Hurricane Georges (1998)

Post your answer in the reply section of our post containing this article’s link!

Puerto Rico.

September 6th, 2017—it is a date that evokes exhaustion from tropical forecasters, horrified awe from weather enthusiasts, and traumatic evocation for the many thousands of people who experienced an unspeakable measure of fear, destruction, and obliteration. It were the people belonging to the latter, whose lives had been uprooted with a shovel, and tossed carelessly into a wheelbarrow. In the blink of an eye, so many had been left homeless, numb, distraught; and above all else, scared. Scared of how merciless nature had suddenly become. Scared of how narrowly they’d just brushed the black shadow of death. Scared, of where they were going to go next, now that their islands’ modernity had been erased from the map.

But for as many people who were dealing with the cataclysmic aftermath that Hurricane Irma had triggered throughout the Leeward Islands, they were outnumbered ten-fold by the people whom were destined to be the next victims of the great cyclone’s treachery. As the sky began to crumble around the Greater Antilles, their time for preparation came to a grinding halt. Irma, was now upon them.

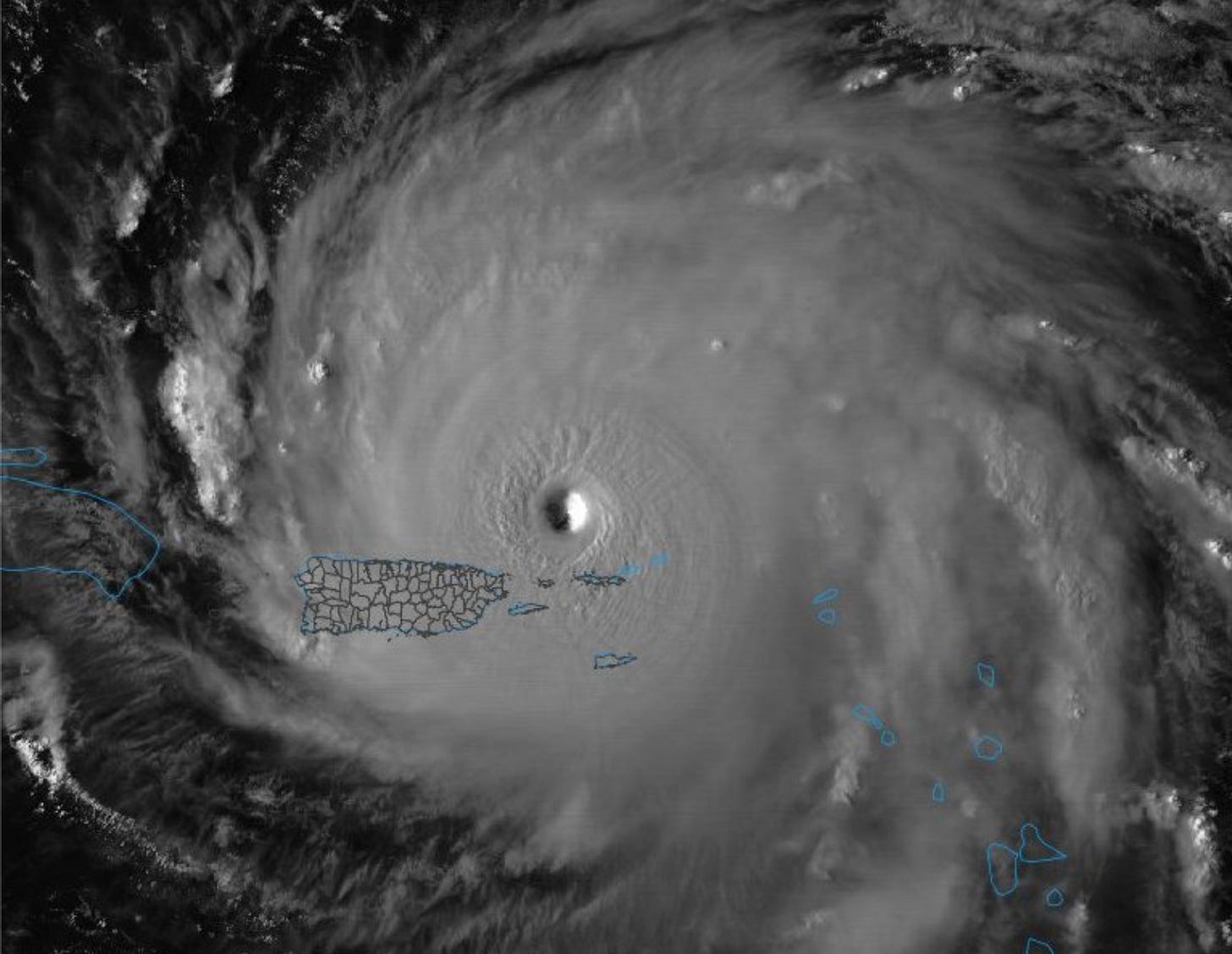

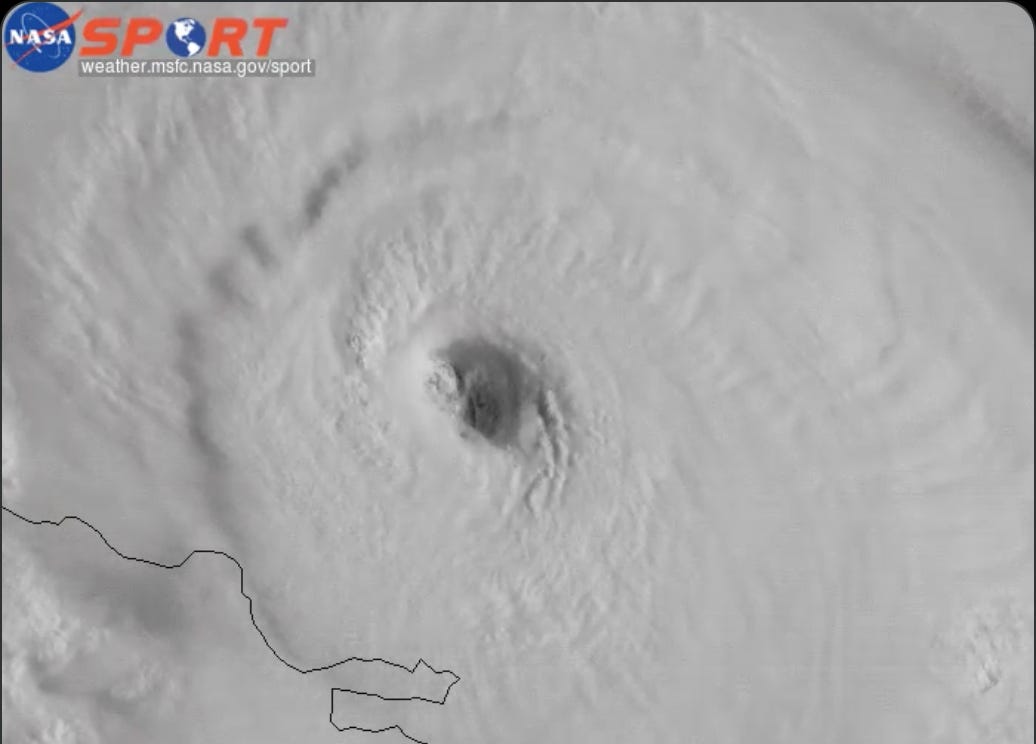

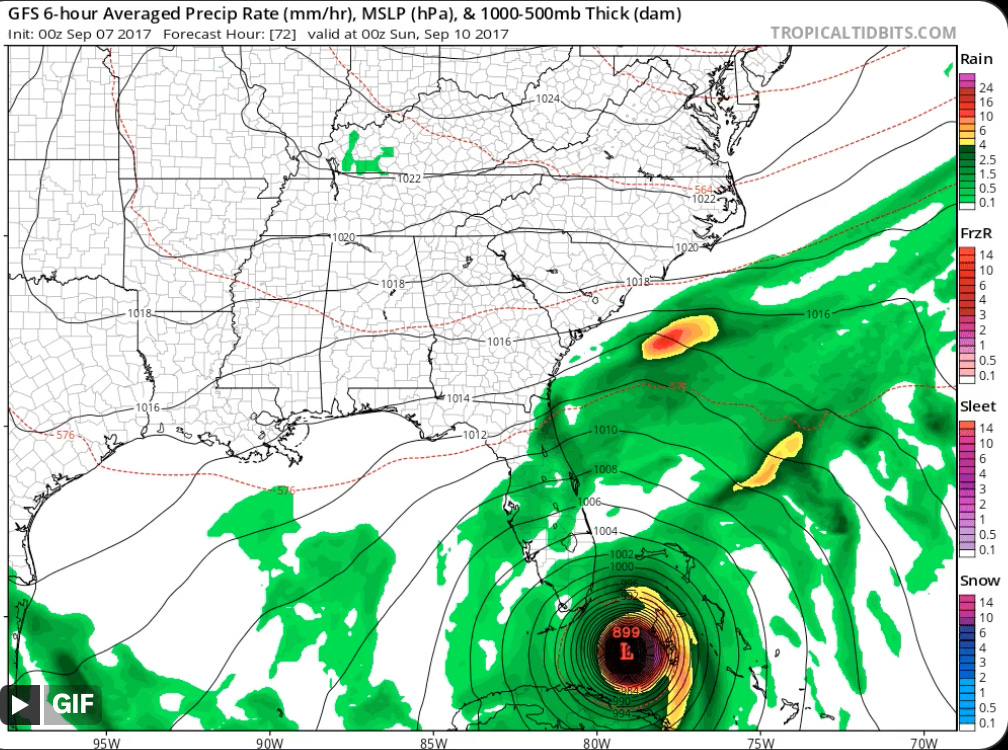

Earlier that day (September 6th), during her landfalls in St. Martin and the British Virgin Islands, the Hurricane’s central pressure had actually weakened slightly off the <916 millibars that had been observed directly on Barbuda. However, by late afternoon, Irma’s core started deepening a second time, again down to a surface air pressure of 914 millibars. This occurred despite the very clear presence of two eyewalls implanted in the storm’s arctic-cold CDO, a feature revealed when Irma came within range of Puerto Rican radar.

While no landfall or core-strike was forecast for Puerto Rico, the Hurricane’s intimate proximity to the U.S. territory nevertheless resulted in dangerous, cyclonic conditions over the heavily populated island. The most immediate and serious impacts were felt on the Puerto Rican municipalities of Culebra and Vieques—small, offshore islands east of mainland Puerto Rico, and west of the Virgin archipelago. Here, Irma’s southwestern eyewall quadrant stiffly grazed by as she churned to the northwest, instigating wind gusts up to 111 mph, overthrowing water and electrical services, and destroying ~30 properties. With just a single telecommunications tower on the island, it took several hours after the storm’s passing for contact to be reestablished with Culebra.

For mainland Puerto Rico, the worst conditions were felt the closer one approached the island’s northeastern corner. While neither of Irma’s double-eyewalls crossed shore, sustained winds of tropical storm-force, with gusts exceeding 70 mph, were recorded in numerous locations. This may not sound as flashy as the extreme wind speeds suffered by the Leeward Islands—and it’s not—but this was still enough to inflict major damage to Puerto Rico’s acutely penurious and fragile electrical grid. The power outage numbers quickly piled up, and soon amounted to a staggering 1.1 million customers without electricity (out of the 1.5 million total households in Puerto Rico). Compounding these problems was the wringing out of Irma’s very heavy outer rainbands over the island’s mountainous terrain, causing rivers to burst from their banks, and extensive flash flooding to ensue. Over 13 inches of precipitation was recorded in the city of Bayamón, with many other locations approaching double-digit totals as well. Several mudslides were reported. Trees were uprooted and collapsed by the blustery winds, with 72 roads becoming impassable due to vegetative debris falling across them. Most structures were able to survive these conditions fairly well; however, up to 50 homes were still listed as completely destroyed in the aftermath, likely from inland flooding.

Overall, Puerto Rico had dodged a bullet; and apart from their power grid, the damage from Hurricane Irma’s flyby was relatively manageable.

At the stroke of midnight later that evening, September 6th finally came to a shuttering close, ending what would become one of the most infamous days in Atlantic Hurricane history. In that single, 24-hour period, much of the ~300 miles between Codrington, Barbuda and San Juan, Puerto Rico had been butchered by the strongest landfalling Hurricane since the 1930s. Of the most extensively damaged islands, exactly 301.5 square miles of lush, tropical forests had either been chopped down by hellishly strong wind gusts, or burned away by corrosive saltwater mist in the air; and the corresponding human infrastructure, was nearly eradicated.

September 7th—She Has to Weaken, Right?

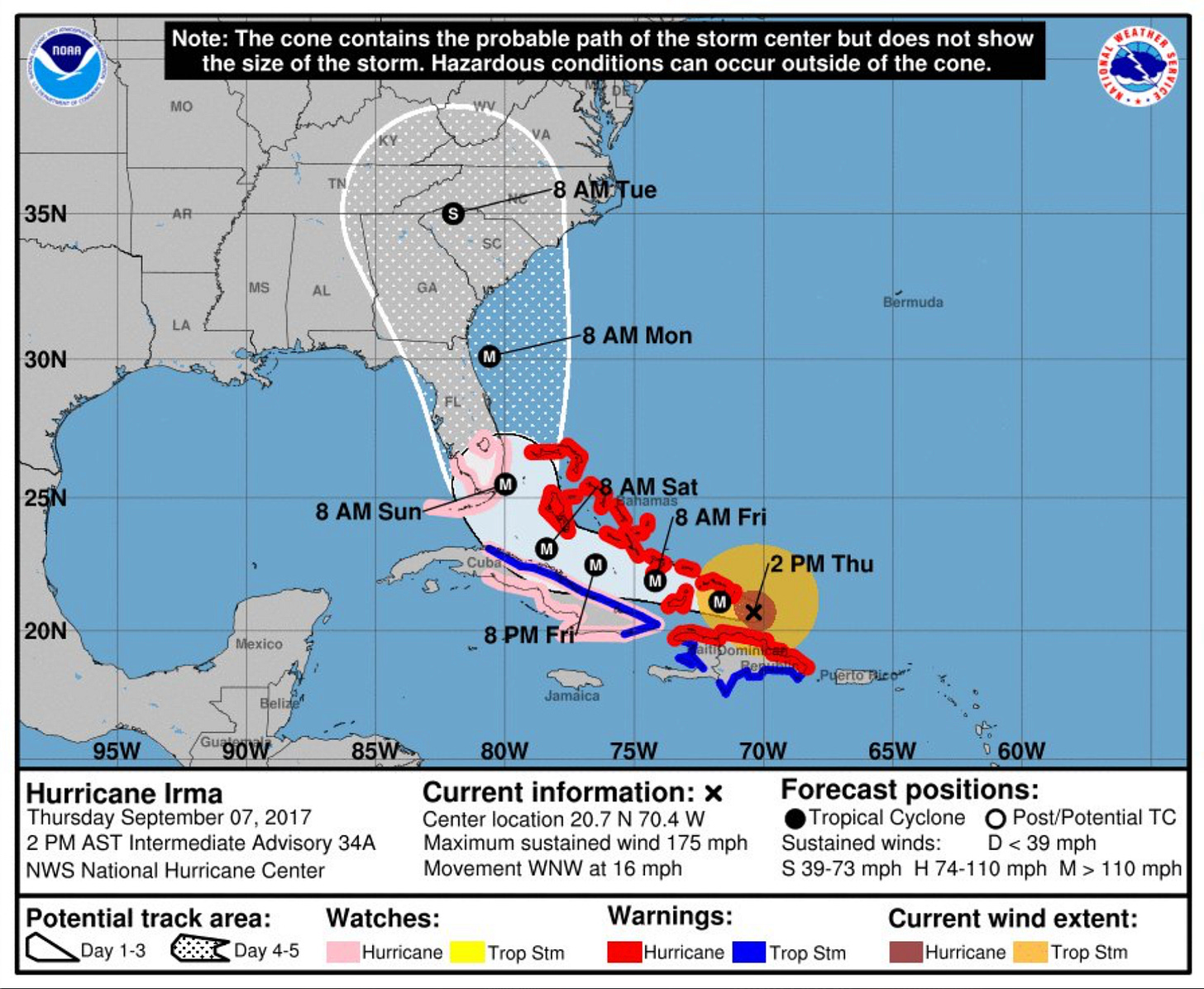

When the calendar clocked over to September the 7th, greater scrutiny on Hurricane Irma’s oncoming track was being paid. As early as September 4th, the storm’s 5-day forecast cone had included the U.S. state of Florida within it, displaying a very flat, initial track that would’ve taken Irma just above the Greater Antilles and through the Straits of Florida. However, by the time Irma was making landfall over Virgin Gorda, BVI, her track was taking a drastic change on the back end. Instead of traveling in a linear, west-northwestward path into the Gulf of Mexico as first thought, a shortwave trough moving into the southeastern United States was going to pick up the Hurricane, and bend her like a fishing hook to the north. This resulted in a forecast cone showing a landfall right up the spine of Florida, through Islamorada and Everglades National Park.

Nonetheless, this was still five days out of where Irma was currently churning, and the spaghetti models were spread from a potential landfall in New Orleans, Louisiana, to a trajectory that curved the storm away from the continental United States entirely. But the following day, on September 6th, the latest forecast tracks put out by the National Hurricane Center could not be ignored. At this time—when Irma had begun raking Puerto Rico—her new, predicted landfall location took her straight into the major metropolitan city of Miami, Florida. More alarmingly still, was that 24 hours later, on the 7th, this terrifying prediction had remained more-or-less rock solid.

It wasn’t just the potential landfall/extremely close parallel scraping of Miami that made this particular forecast so concerning. Under this track, Irma would carefully thread the needle between Cuba and the largest islands of The Bahamas, meaning that her core would escape any major land interaction. If this were to occur, then the Hurricane would be able to run aground in Miami with a seawater mass that had been uninterrupted in its accumulation first began, back when Irma formed thousands of miles to the east, in the Central Atlantic. To make matters worse, the sea surface temperatures (SSTs) within the triangle of Florida-Bahamas-Cuba, were exorbitantly warmer and more energetic, than anything Irma had feasted on in the open Atlantic up to that point. And when taking into consideration the fact that the legacy of Irma’s internal dynamics were bizarrely favorable for longevity at high intensities (given that when Hurricanes reach Cat 4-5 status, they almost always fluctuate in strength, due to the ebb and flow of EWRCs), many learned, and professional meteorologists feared Irma could be even stronger than what would already be a cataclysmic 150 mph sustained wind speed at landfall.

To fully understand how dire this situation was, think back to the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane (the very storm Irma had conjured up memories of in 2017, as she was the first Atlantic cyclone since that Great Depression-era storm to strike land with winds of 180 mph or higher). It was a small, tightly coiled, and hyper-intense Hurricane that cut through the Florida Keys before running up the State’s Western/Gulf Coast (an eerily similar track to Irma’s September 7th forecast). In the narrow areas where Labor Day’s eyewall hit, the conditions were so ferocious, that trains were knocked sideways off their tracks, and people were barbarously sand-blasted to early, gruesome graves. However, go more than six miles in any direction out from the storm’s center, and the effects of the Labor Day Hurricane were much less severe, because her radius of gale-force winds was extremely compact (with an eyewall width of just 5.8 miles across).

Now, imagine those unimaginable wind speeds that knocked over trains, and peeled off human skin like a knife on an apple, again—but this time, in a storm whose Hurricane-force winds stretched at least 70 miles across, instead of merely ~6. And now, imagine this impacting the millions of people who inhabit the cities of South Beach, Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Naples, and so on; as opposed to a few, ramshackle towns in late 1930s Florida Keys, inhabited by only a couple thousand people (most of whom, veterans of World War I). It was an unthinkable, nightmare scenario.

But regardless, even if Irma didn’t re-intensify to 175+ mph—even if, for the first time in her life, her internal structure did not cooperate, and weakened her to something like a mid-range Category 4—the consequences of if she did not touch land again before hitting Florida, would nevertheless result in enough damage to rival the price tag and notoriety of 2005’s Hurricane Katrina. Thus, the only remaining X-factor that stood in the way of Irma fulfilling this worst-case-scenario or not, was whether she stayed north of Cuba, or if she stayed westward enough to make landfall there, and weaken before entering the boiling Straits of Florida.

While U.S. forecasters gambled with the odds of a Cuba landfall in the coming days, the island of Hispaniola was the latest country getting trawled by Hurricane Irma’s effects. Like Puerto Rico, the understanding was that they were going to dodge a bullet, with Irma’s eyewall steering just clear of their northern coast. Even still, intense rain and winds would end up lashing the large, bulky island anyway (particularly on the northeastern side of the Dominican Republic).

The pass began overnight on the 7th, and extended into the afternoon. During this time, Irma’s hard run-by of Hispaniola’s harshly jagged terrain (legendary for its reputation of adversely affecting any tropical cyclones that stray too near) resulted in a loss of symmetry in the icy cloud tops of her CDO. Southern outflow channels were constricted, and Irma’s core pressure began to rise; astonishingly, however, significant weakening did not transpire, with the storm’s strength only lessening to 175 mph/922 millibars (despite a much more lopsided appearance on infrared satellite).

The worst impacts on Hispaniola were felt in Haiti, where Irma’s trailing rainbands triggered mudslides and flash flooding down the slopes of heavily deforested mountains. But to Haiti’s north, the Turks and Caicos Islands were not going to be so fortunate as to avoid a direct hit. By 7:30 pm AST, September 7th, Irma’s eye closed in on landfalls over South Caicos and Ambergris Cay; while the strongest of her Cat 5 winds, contained within the northern eyewall, rammed through the rest of the archipelago. Once again, whole hillsides of forests were obliterated, and 75% of roofs on South Caicos were torn away. The Turks and Caicos had become the next domino in the row, to fall.

September 8th—History in the Making.

September 8th, 2017—late into the dusk, of a Caribbean twilight. An oppressive stench clung to the sultry wetness of the air; a stifling aroma of pulverized wood, organic rot, and something unidentifiable that was reminiscent of decaying fish, now haunts not just the atmosphere of one island, but over a dozen. They had been Goddesses of the natural world—but now, were felled to their knees in a degree of ruin that looked like the war-torn remains of the 1940s’ Island Hopping battles.

Over 9,000 miles and 73 years removed from those terrible conflicts, Hurricane Irma was embodying her own war of barbaric ramifications; and as she rolled steadily closer to the neon lights, steamy swamps, and bustling cities of south Florida, the only question remaining was how viciously she was going to wage her final dogfight.