It was a Tuesday afternoon in early September, 2017. On the rounded shores of the tiny, Caribbean island of Barbuda, people stood on the seashell snow of the beaches’ sands. They looked out over the coastal lagoons surrounding these beaches, turning the soft skin of their faces into the saline breeze. The air, here, was tinged with fear; and the water didn’t have its usual, aquamarine luster, and was instead clouded with a more ominous, sandy albedo. Tropical rain showers had been coming and going throughout the day; their drops of water staining everything with a wet coating of anxiety, uneasiness, and foreboding.

By the 5th day of September, the people of Barbuda knew that a powerful Hurricane was just beyond the horizon—for them, these storms were no strangers. Barbuda lies at an intersection of the open Atlantic’s tropical hunting grounds, where Cape Verde storms can strike the island from the east, as they travel westward off of Africa. Thus, the island’s history with Hurricanes is storied, and well-chronicled.

But when 2017’s Category 5 Hurricane Irma came knocking on this small island’s doorstep, it quickly became clear that they were about to be at the mercy of a storm, like no other. This Hurricane’s magnitude was immense; her winds, squealing; her curves, insatiable; and her heart, burning with a deep hunger for vegetative flesh, and human settlement. It would be through a Grand Tour of unimaginable destruction—a tour, spanning 14 different countries and overseas territories—that Hurricane Irma was going to redefine our understanding of just how powerful Atlantic Hurricanes can become… and the sweeping breadth of life-altering damage, that they can inflict.

There’s a tacit rule of law that governs over the waters of the Atlantic Basin. For every sub-region and oceanic sector, there is a certain expectation—a stereotype, even—for the storms they spawn. These expectations range from a storm’s average longevity; the historical times of the year when their cyclogenesis is most probable; the likely direction of said storm’s movement; and, most importantly, their intensity ceiling.

Ask any meteorologist, or seasoned tropical weather enthusiast, and they can divulge to you the subtleties, tendencies, and traditions of each independent region of the Atlantic. Looking for a propensity for rapid intensification up to landfall? The Gulf of Mexico, with its warm coastal waters and deep currents of heat energy, is your place. Wondering which waters are capable of supporting some of the strongest Hurricanes of all time? The Caribbean Sea is likely the place to be. Or maybe you want to slow down, feel the wind and the rain making your skin chilly—not trying to peel it off. In this case, look out in the direction of the Central Atlantic, where most storms are weak, erratic, and have a genetic inclination to loop around in meaningless circles.

Then, there is the Tropical Atlantic; also known as the Main-Development-Region, or MDR, for short. It is here—in the vast, cosmic expanse of the Atlantic’s most open of waters—where West African-spawned cyclones can come to grow into some of the largest storms in the basin. During years with favorable conditions, (such as sufficient instability, moist air, and low wind shear), the MDR is usually the centerpiece of tropical excitement, becoming most active during September (which is, historically, the peak month for the Atlantic Hurricane Season).

There are many environmental factors that make the MDR one of the most specifically active regions in the world for tropical cyclogenesis, but right now, we are going to focus on these waters’ oceanic heat content. It exists as a sort of happy medium between the tepid, temperate latitudes, and the extremely warm deep tropics(Caribbean/Gulf of Mexico). The potential energy stored here is more than enough to sustain massive, Category 4 Hurricanes—many of them, reaching sustained winds over 145 mph, which qualifies as the high-end of the Cat 4 spectrum. But it’s in this wind-speed range (145-155 mph) where a line has typically been drawn in the sand. Most of the time (even during seasons that host above-average activity), the MDR’s waters either don’t have the depth of heat to sustain a Category 5 Hurricane (a criteria met at 157+ mph), or they simply aren’t hot enough to begin with.

That’s not to say that stranger things (no pun intended) haven’t happened before, on more than one occasion.

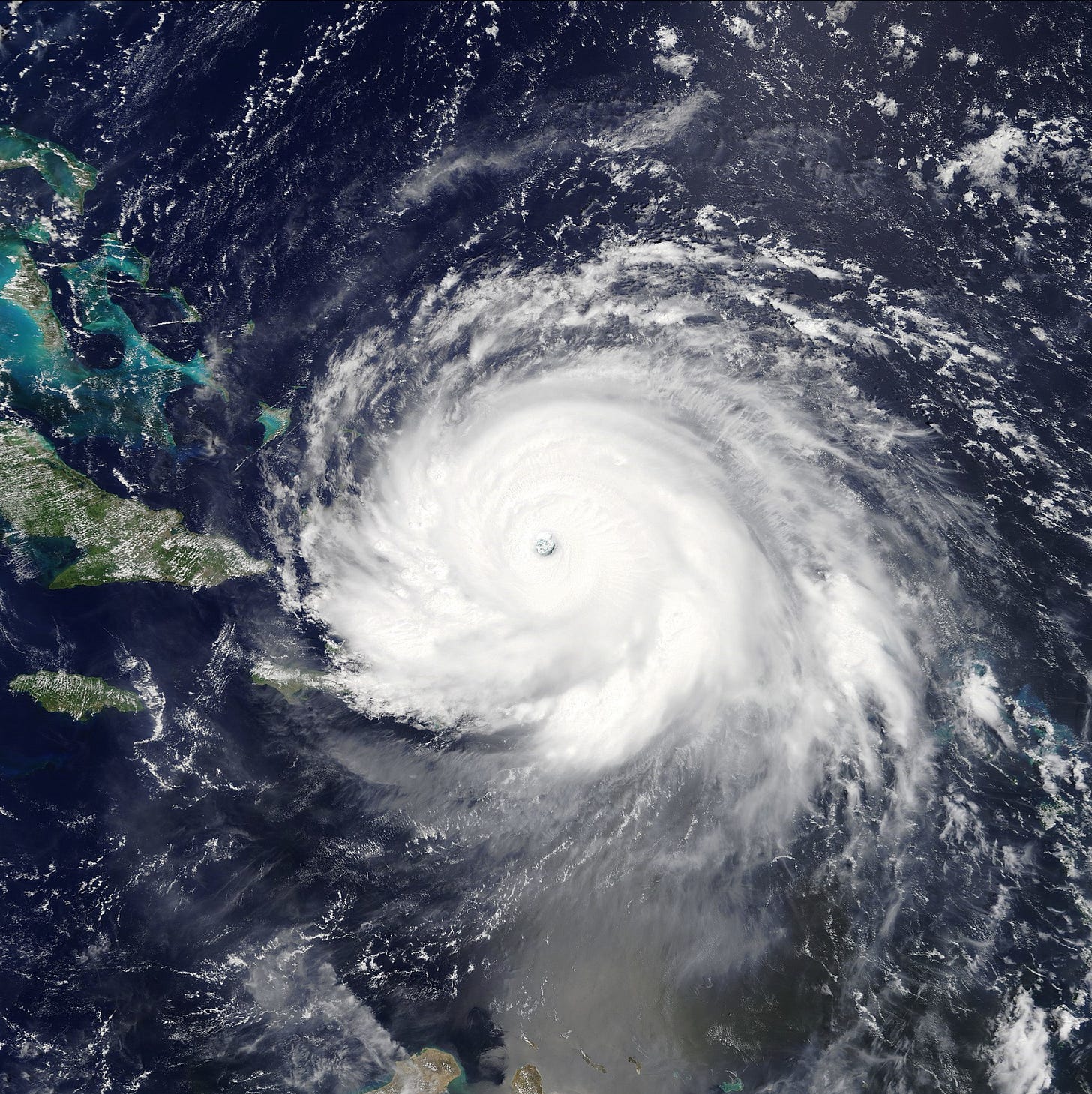

The 1932 Bahamas Hurricane, to start, was the first confirmed cyclone with winds greater than >157 mph that was observed outside of the Caribbean or Gulf of Mexico. This storm was followed by the Cuba-Brownsville Hurricane just a year later, in 1933, whom tapped a peak intensity of 160 mph/930 millibars while passing near the Turks and Caicos island. In 1938 and 44, the “New England” and “Great Atlantic” Hurricanes also achieved Category 5 status in the open Atlantic seas (once again, in the general proximity of the Bahamas). It would take until 1953, however, for a Category 5 (Hurricane Carol) to be recorded in the true Main Development Region of the far eastern Atlantic, outside of the Lesser Antilles’ longitude. The rest of the open-Atlantic-Cat 5s subsequent include Esther (1961), Hugo (1989), Andrew (1992), and Isabel (2004).

Now, at this point, you’re probably beginning to think that this is quite a few storms of the maximum intensity on the Saffir-Simpson Scale in the open Atlantic; and you’d be right. You may now be asking, then, why I’ve gone to all this work to construct a sort of Hatfield-McCoy distinction between the Atlantic and the Caribbean/GoM. Therefore, I’m going to tell you.

Firstly, let’s consider, specifically, these storms’ maximum strength. If we calculate the average (using only storms pre-dating the 2017 season) peak wind strength of a Category 5 Hurricane observed in the open Atlantic (this is our Randolph McCoy, if you will), we come out with a value of 162 mph, and an average minimum pressure of ~924 millibars. Now, let’s compare this to the average strength and intensity of Category 5s spawned in William Hatfield’s Caribbean/Gulf of Mexico Basins. For these outputs, we get an average of ~172 mph/913 millibars—thus, clearly showing Category 5s spawned in these regions to be significantly more powerful than their open-Atlantic counterparts. Moreover, only nine of the thirty-three Category 5 Hurricanes recorded before 2017 materialized outside of the Caribbean/GoM (while just one (Andrew) attained winds higher than 160-165 mph).

Additionally, if we look at the coordinates where these nine open-Atlantic storms were at when they hit Cat 5 intensity, six of them peaked within the approximate bounds/area of the so-called Bermuda Triangle. This puts them in (at minimum) close proximity to the Gulf Stream (an infamously strong ocean current that milks and squeezes out warm waters from the Gulf of Mexico, and channels them up the East Coast of the U.S.).

In conclusion, this leaves us with just three storms—Isabel, Hugo, and Carol (in that order, left to right)—that achieved Category 5 intensity in, or near, the eastern Atlantic’s Main Development Region.

Therefore, it’s safe to say that, while the MDR represents the primary breeding ground for Hurricanes in the Atlantic, and is more than capable of supporting high-level Cat 4-to-Cat 5 cyclones, it seemed that it just doesn’t have the vitality, to consistently bear the conditions necessary to bolster ultra-powerful Hurricanes. 2003’s Isabel is the only major outlier here, when she peaked at an impressive 165 mph/915 millibars (and held it for ~30 hours at that). Given this historic precedent, it was always presumed to be extremely unlikely that a Hurricane of Cat 5 strength could strike the Lesser Antilles from the east. And if you were to conjecture of a storm of even higher intensity—a storm analogous to the greats of the past, such as Wilma (185 mph/882 mb.), Gilbert (185 mph/888 mb.), Rita (180 mph/895 mb.), etc.—these conjectures would likely be dismissed as fear-mongering.

But now—if we return ourselves to those early days of September 2017—we see a reaving gang of thunderstorms, borne from the heart of Africa’s rainforest interior, that was about to challenge everything we thought we knew about the MDR’s so-called intensity ceiling.

August 27-September 4—The End of the Beginning.

On August 27th, 2017, Hurricane Harvey—now a tropical storm—had been sitting over the Texas coast for 2 days and counting, unloading dozens upon dozens of inches of rainfall over the city of Houston (and its surrounding bayou fiefdom), in the process. It was an unfolding flooding catastrophe that the U.S. hadn’t seen the likes of since Hurricane Katrina (2005) herself.

But while the world’s eyes were glued on what was quickly developing into one of America’s costliest cyclonic disasters in history, the National Hurricane Center was already swiveling their periscope to a perturbed area of weather, tiptoeing the mangroves of the Senegal/Guinea-Bissau border. Over 5,000 miles away from Houston and Harvey’s ongoing wrath, the coffee seeds of a new storm were already brewing in a pot of boiling instability.

The disturbance cannonballed into the Atlantic water soon thereafter, on the 27th, and she would pass straight over the Cape Verde Islands on her way into the MDR. Three days later, the first advisory for Tropical Storm Irma was released on the morning of August the 30th. To inaugurate 2017’s newest spinning-top, the NHC wrote:

BULLETIN

Tropical Storm Irma Advisory Number 1

NWS National Hurricane Center Miami FL AL112017

1100 AM AST Wed Aug 30 2017

…IRMA FORMS OVER THE FAR EASTERN ATLANTIC…

…NO IMMEDIATE THREAT TO LAND…

SUMMARY OF 1100 AM AST…1500 UTC…INFORMATION

LOCATION…16.4N 30.3W

ABOUT 420 MI…675 KM W OF THE CABO VERDE ISLANDS

MAXIMUM SUSTAINED WINDS…50 MPH…85 KM/H

PRESENT MOVEMENT…W OR 280 DEGREES AT 13 MPH…20 KM/H

MINIMUM CENTRAL PRESSURE…1004 MB…29.65 INCHES

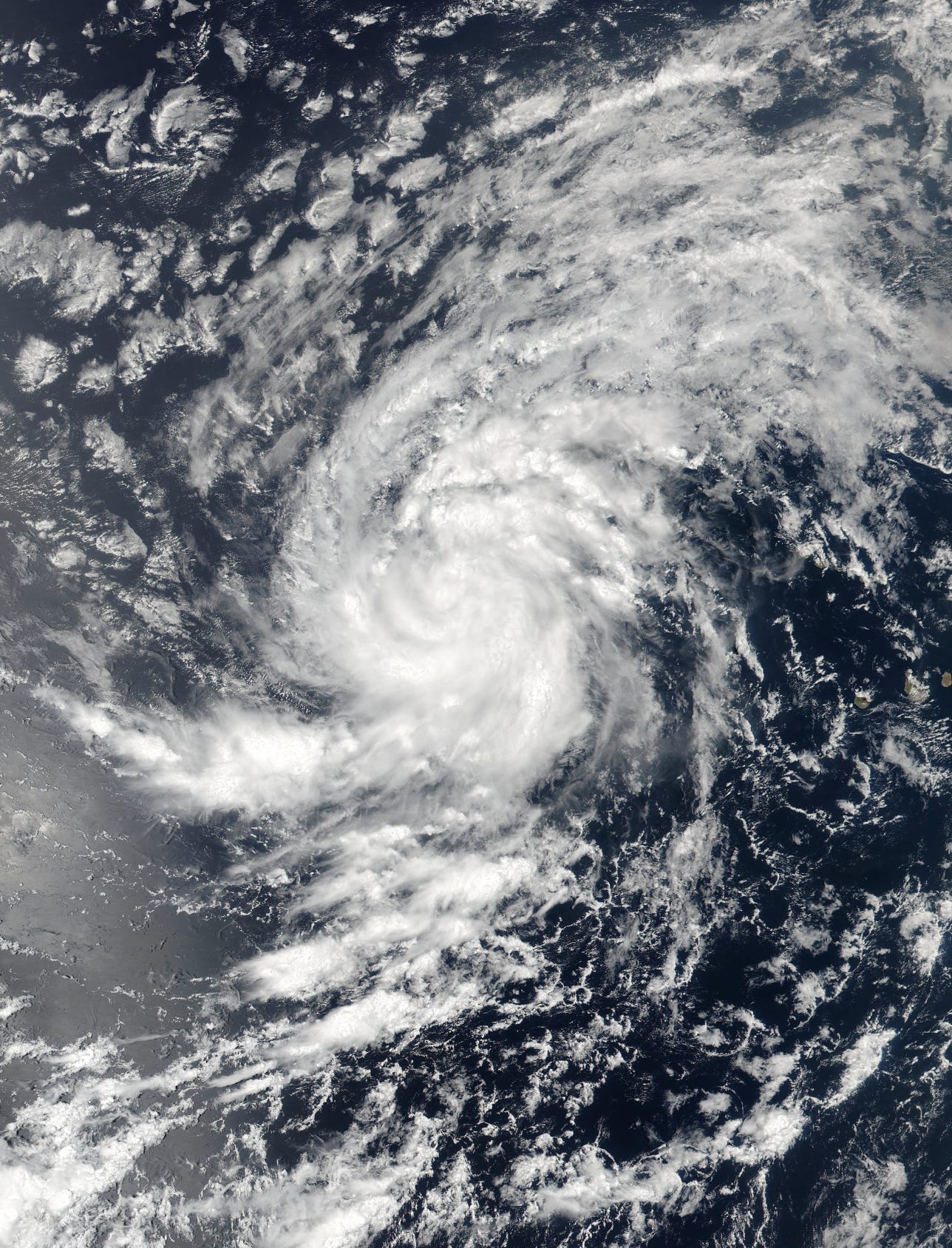

Leading up to this point, the system’s showers and thunderstorms had clearly been eager to accept the effects of the Coriolis Force. Banding features were wrapping in a clear and definitive spiral pattern, promptly establishing an area of low pressure that looked like a divot on the golf green in the atmospheric gradient. Irma had formally embarked on her journey westward.

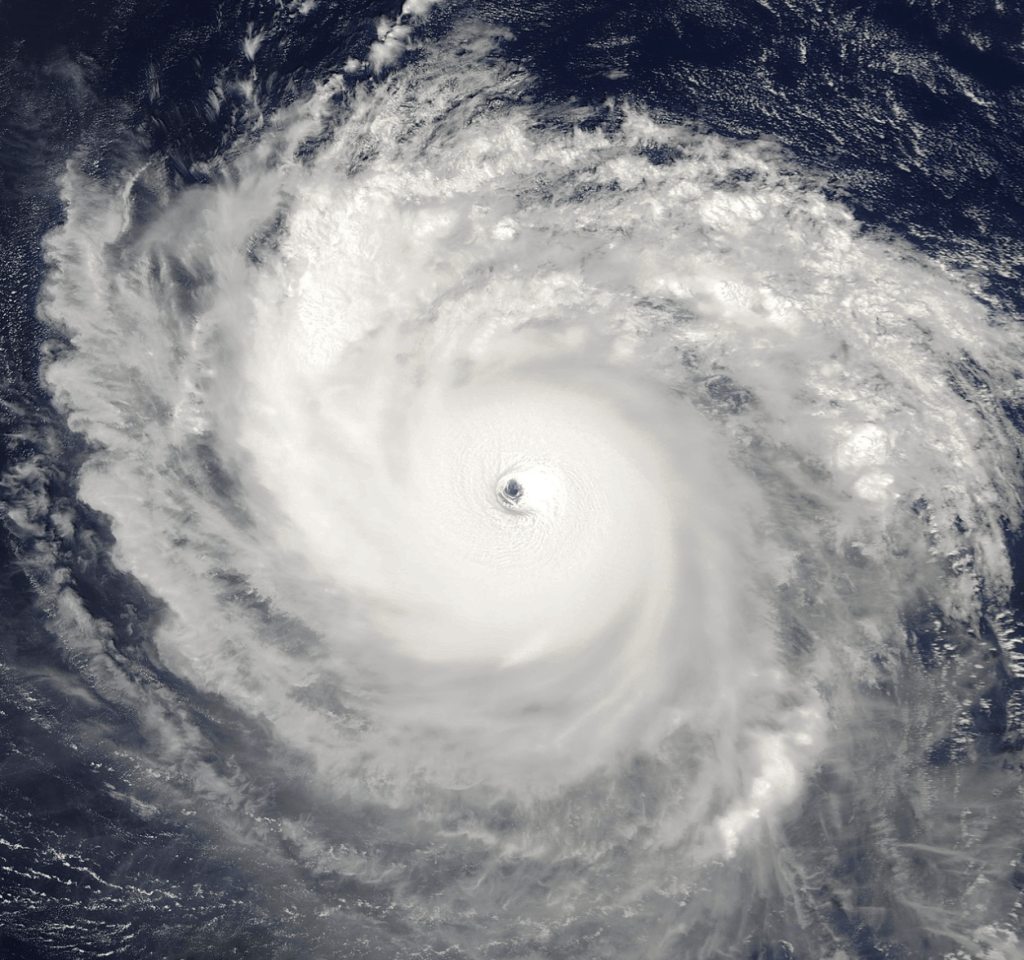

As she made her way through the lonely fathoms of the far Eastern Atlantic, Irma’s lurid convection started to get smoothly swirled by a mixing beater of cruelness and brilliance. With a high-pressure anticyclone present over the tropical storm, the system’s chest swelled, as her poleward lungs filled with moist air. Thunderstorms intensified and melded into a formative Central Dense Overcast (CDO). An air bubble in the center of this creamy concoction popped open, giving Irma a slovenly eye. Later that day, on August 31st, she was upgraded to a Category 1 Hurricane, just 30 hours after first being named. This pace of organization—especially for a storm in her younger stages (during which intensification is typically the slowest, because tropical storms simply aren’t born with adequately stacked convective layers), was nothing short of exceptional.

Wolfing down every last morsel of warm, evaporated water vapor that she could stuff into her bulging core, Irma’s upgrade to Hurricane status only bolstered her eagerness for rapid intensification. Core cloud tops began to freeze colder than a meat locker. The outflow channels fanned out like a delta of estuaries, all feeding into a single, lake-like mass in their center. And in the dark, murky depths of this lake, the currents were spiraling, churning; a monster prowling in the black of the abyss. Vortical hot towers school in a rotating mass, attempting to escape the voluminous jaws of that monster in the abyss. Alone, these hot towers are nothing more than singular, rapidly rising thunderstorm updrafts; but when merged together, they become the framework for a Major Hurricane’s core cloud structure.

As a result, Irma’s eyewall completed, and rapid intensification officially commenced. By 5 pm AST, August 31st, she reached maximum sustained winds of 115 mph, and a minimum central pressure of 967 millibars—making her a Category 3 Major Hurricane. In just her first 48 hours of existence, Irma had already gained 65 mph since taking off from the starting line. Her compact size made this sudden bout of strengthening possible, with tropical storm-force winds only extending out 80 miles from the center.

Once reaching Category 3 status, Irma took a moment to sit and rest from her extraordinary sprint. She was in the awkward phase of her teenage days, and thus did not possess the wherewithal to continue onward with intensification. She would have to wait to mature into the perfect, physical specimen of vitriolic beauty that awaited her in young adulthood.

For over 30 hours, Irma hardly moved an inch in intensity, before an eyewall replacement cycle (EWRC) was finally triggered. As anticipated, this incited a temporary weakening phase while the Hurricane’s internal dynamics restructured themselves.

In the meantime—during which, our intensity ensembles tried to keep up with Irma’s recently shifting gears—some computer models were racking their algorithms to try and tie down where Irma was heading. Because a blocking ridge feature had been set in stone across the Mid-Atlantic, confidence was increasing that Irma was not going to be allowed to curve away harmlessly into the open ocean—as is the case with roughly 80-90% of Hurricanes that form in the MDR. By September 2nd, guidance models were quickly favoring their more southerly brethren, indicating that steering patterns were coercing Irma into either skirting, or plowing directly through, the Leeward Islands. Henceforth, in the 11 pm AST NHC Advisory discussion:

The cloud pattern of Irma has not changed significantly in structure

today. The eye continues to become apparent and then hide under

the convective canopy, and this has been the observed pattern for

the past 24 hours or so…

…I hesitate to speculate too much about the environment that Irma is

embedded within. All of the standard ingredients necessary for

strengthening are forecast to be at least marginally favorable, but

none are expected to be hostile for intensification. The NHC

forecast, which in fact is similar to the previous one, continues to

be a blend of the statistical models and the explosive strengthening

shown by the regional hurricane and global models…

…Tonight’s NHC forecast was adjusted a just little to the south of the previous one due to another small shift of the guidance envelope.

-Forecaster Avila

September 5—Blink Twice.

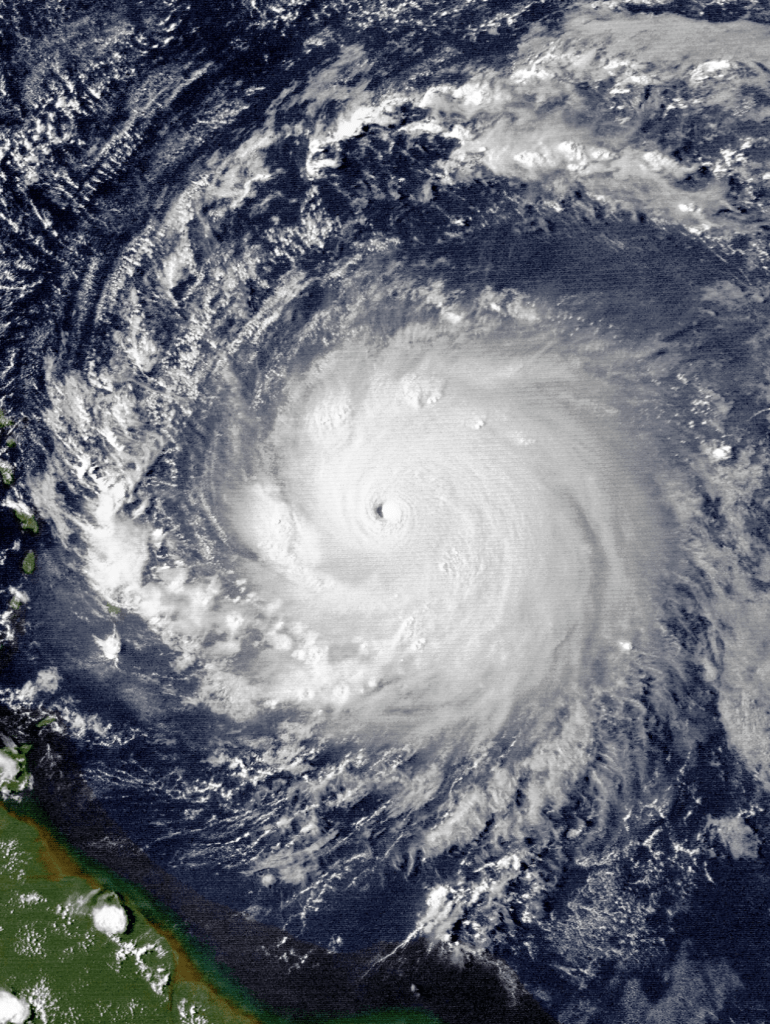

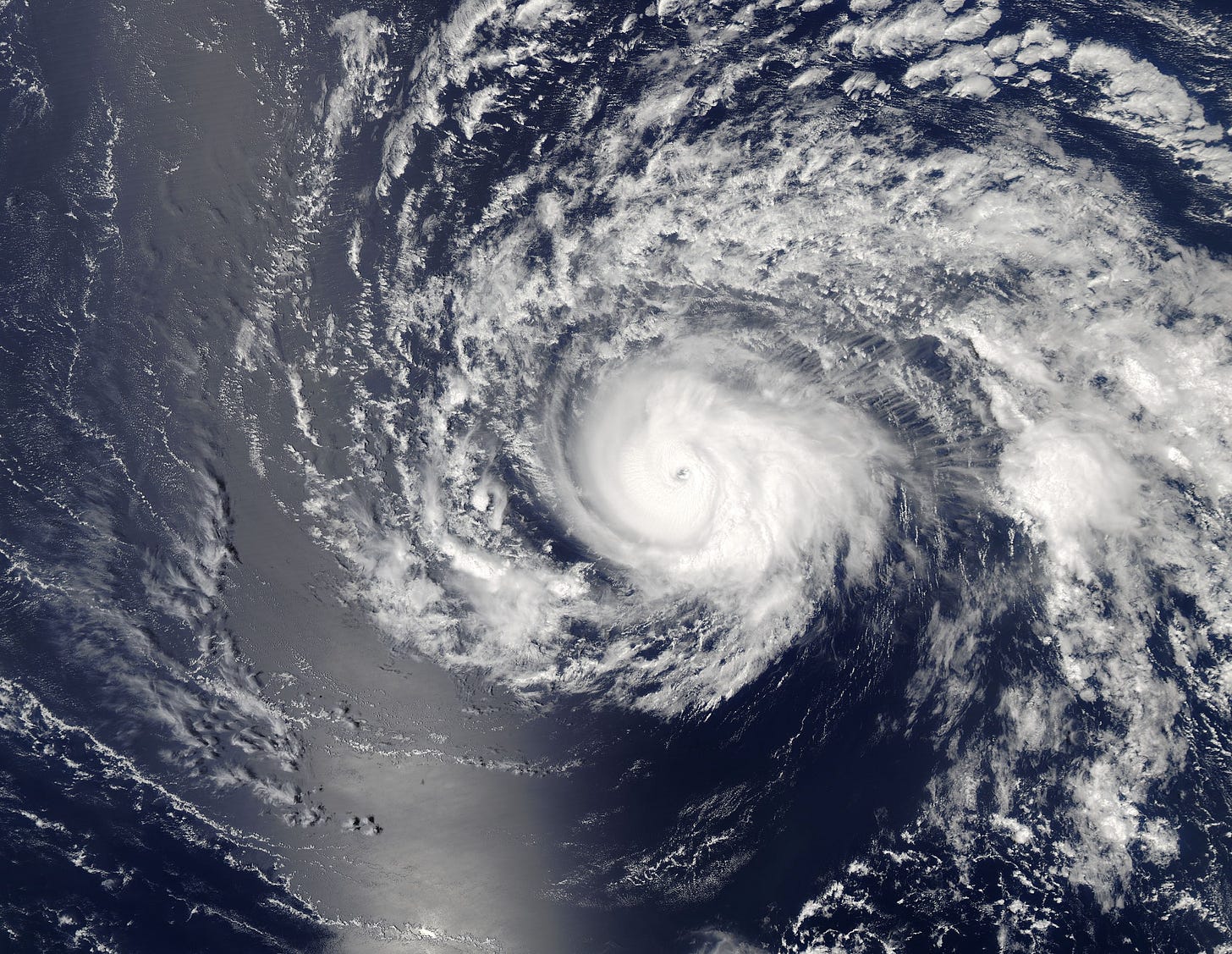

For an astonishing, ~72 consecutive hours, Hurricane Irma’s sustained winds held at a remarkably consistent 110-115 mph, with a corresponding pressure ranging from the high 950s to the low 970s, in millibars. Over the course of this long cruise on autopilot, Irma’s new eyewall, freshly embedded in the CDO, acted as the final catalyst for the Hurricane’s graduation to adulthood. Irma began to fill in, forming the shapes of the mold she’d been desiring so earnestly. This happened in a flash, quicker than the venomous stab of a stingray’s barb.

At the 5 am AST Advisory on September 4th, 2017, Irma continued to be pegged at the same wind speed of 115 mph, correlating to a 961 millibar core (despite her appearance having recently improved from the previous days). By now, confidence had increased in the more southerly tracks, and Hurricane Warnings had come up for portions of the Leeward Islands. In the NHC’s latest forecast cone, Irma was predicted to at least hold, or possibly intensify, on her way to ruffling Antigua, Barbuda, and eventually, the Virgin Islands—with a potential peak, as a 140 mph Category 4.

But when the next update dropped 3 hours later, at 8 am AST, it was obvious that the intensity forecasts had already been too conservative. While Irma’s winds rose only slightly in the new advisory, her core pressure had plummeted 14 millibars, to a value of 947. Hurricane Hunter aircraft reconnaissance also found that the storm’s eye and total wind radius were expanding concurrently with the strengthening of the eyewall. This contradicted the typical inverse relationship seen between a tropical cyclone’s wind strength, and their gale-force winds diameter.

As recon continued to investigate the storm through the day, they began to detect two concentric wind maximums, indicating that another EWRC was preparing to initiate. However, the binary pair of distinct eyewalls disappeared as quickly as they’d congregated; joining forces, and merging to become a single, primary eyewall. This eliminated the wild card factor of the unpredictable nature surrounding the Hurricane’s internal dynamics. Any hopes of an unexpected weakening phase, were quickly dashed.

Thus, with the limitless highway stretching out before her, Irma was fueled, anxious, and loaded for bear. She now had no barriers, nor roadblocks, ahead. The only limit, was the limit itself.

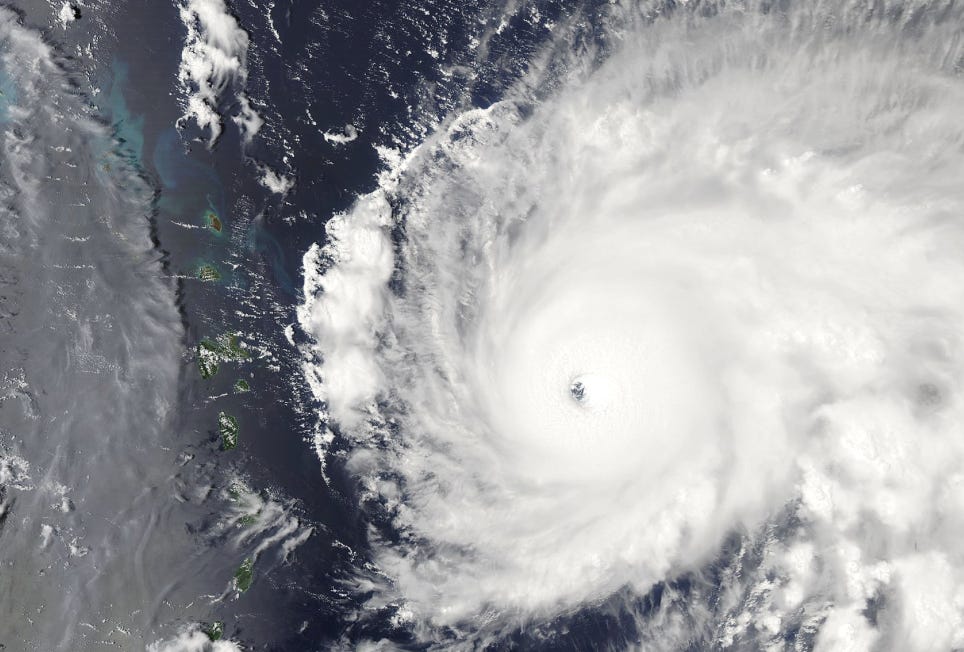

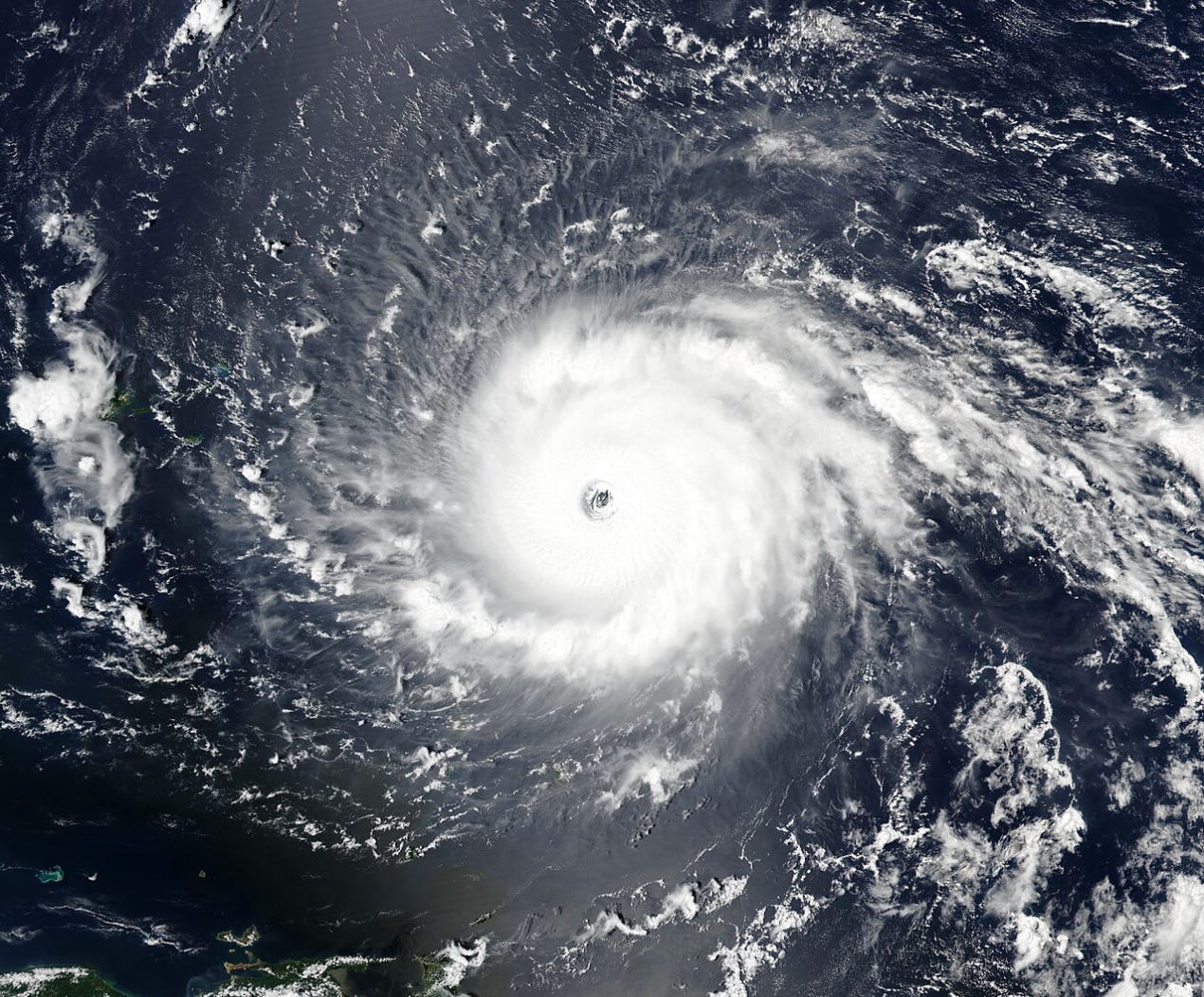

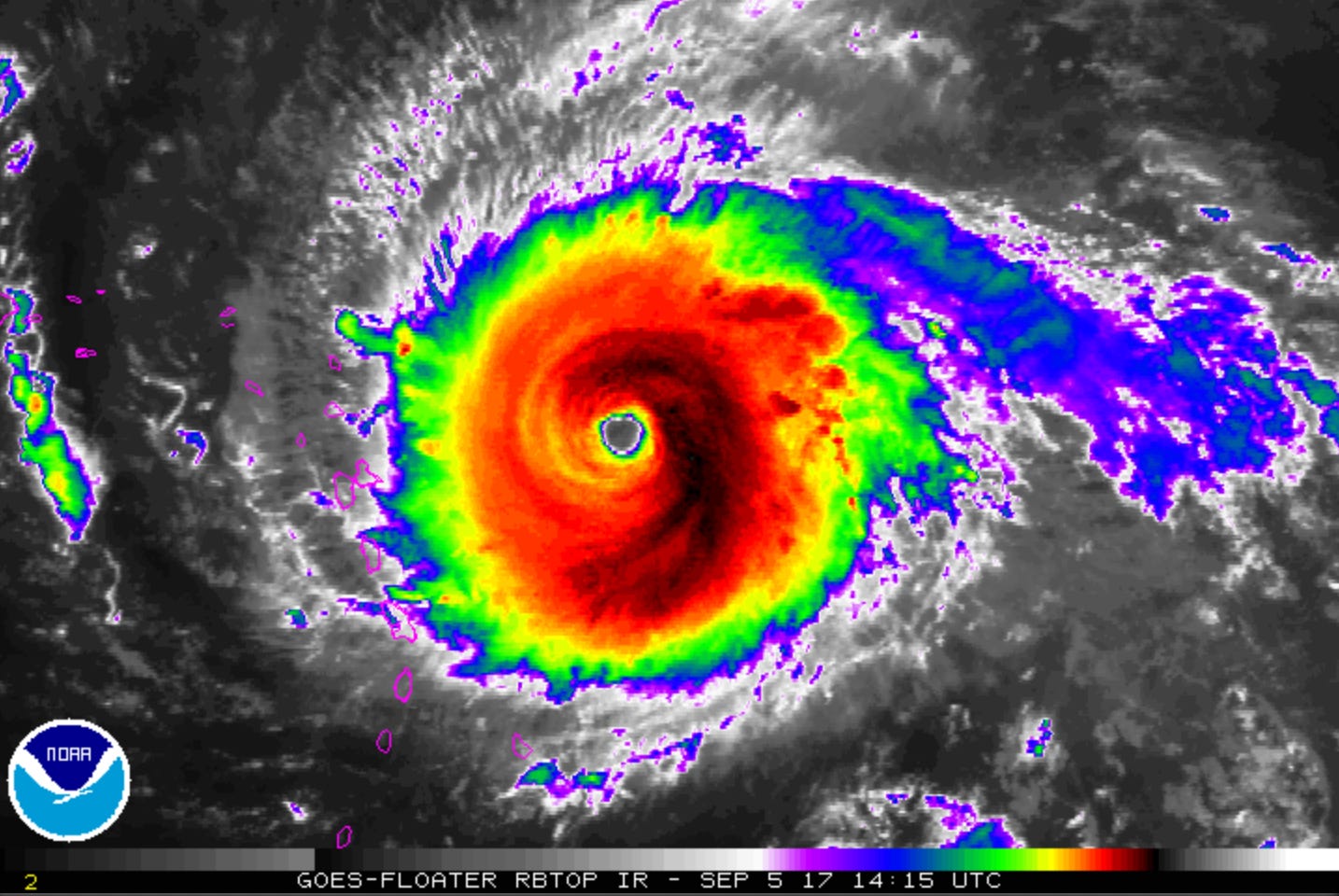

Her icy blocks of intrepid convection crunched together into a frigid, foaming mass exploding outward; like decomposed hydrogen peroxide bursting from the lips of a test tube. Her large eye deepens and shivers, a perfect product of angular momentum slicing through the folds of frosty thunderstorm layers. Her rainbands constrict, strengthen, and coruscate like the arms of a spiral galaxy. After first achieving Category 4 status late in the afternoon of September 4th, Irma’s winds snapped the last rope holding them back. By 5 am AST, September 5th, the eyewall’s dizzying spin had pressed past 150 mph; and by the golden glimmer of an Atlantic, late summer dawn, Hurricane Irma abruptly rocketed to an extremely powerful, and historically unprecedented, 175 mph sustained wind strength. It was in this sudden eruption of flawless ferocity, that Irma did not merely push the envelope, but broke through it like a sledgehammer smashing drywall. And what emerged from that musty cloud of drywall dust, was a storm that clearly believed laws were only made to be broken.

For the people of Barbuda, time was now running thin—and the stakes were higher than ever. There was a wolf at their doorstep, when they’d only had to face scavenging raccoons in the past; and the rabid salivating of the ocean’s waves were a sinister reminder of the vicious jaws closing in around their island. Barbuda’s geography of low-lying terrain, soft scrubland, and massive, saltwater lagoons, made its topography a marshy, easily penetrable tissue for Irma’s storm surge to sink its teeth into. And as the Hurricane churned closer, with record-breaking, and unparalleled force, no structure on Barbuda was safe. There existed no modern precedent; nor preparation; nor appropriate criterion, for the incredible wind speeds they were just hours away from experiencing. It was a situation no Atlantic nation had seen since the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane had cut down the Florida Keys with sustained winds of 185 mph.

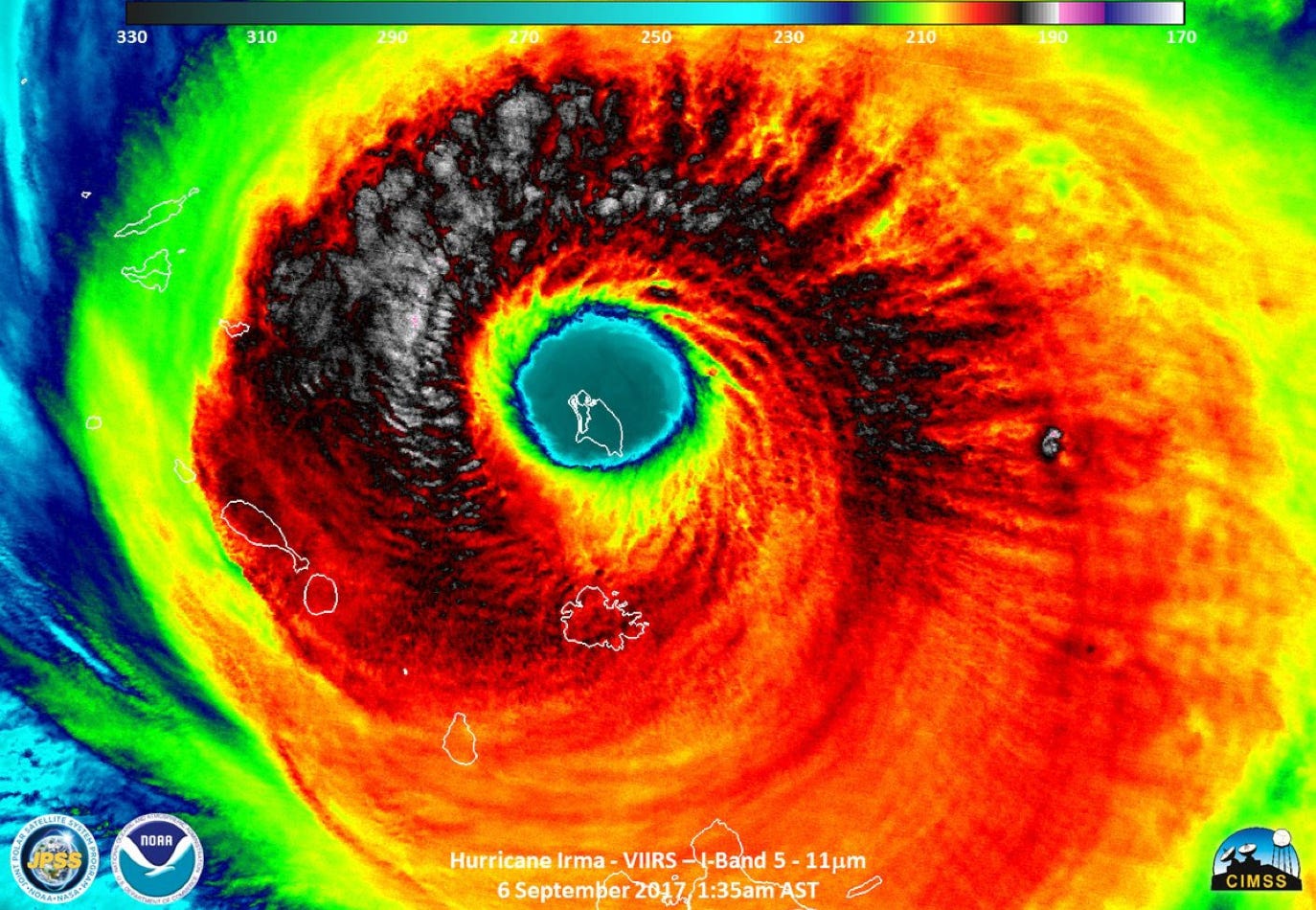

As September 5th’s afternoon wore on, Irma’s incarnation was complete. Taking on an unusual, cleanly annular appearance in the process, the Hurricane finally leveled off her extreme intensification phase. At 180 mph, and 914 millibars, she surpassed Hurricane Isabel (2003) as both the strongest, and most intense, Hurricane ever recorded in the open Atlantic. With very few distinct rainbands left on her periphery, the foundation on which she spun was built on a single, incomprehensible, concrete-white ring of glacial convection. This ring acted as a stalwart hive, while the eyewall were the hive’s soldiers; and at the core of it all, the redoubtable Queen, driving her deadly hive-mind forward, and supplying her tempestuous wind wings, with their despicable motivations.

September 6th—The First Landfall.

Darkness descended upon the tropical woodlands of Barbuda. Across the undulating canopy of green, the rattling croak of frigatebirds echo off the raindrops. In the grasslands sparkled by rain, groups of fallow deer amble through the disquieting twilight, smelling the augury on the billowing wind gusts. On the other side of the island, in the city of Codrington, families retrieve the last of their personal items from their lawns, and batten down the hatches to their cinder block homes. They switch on their radio sets, hoping, unrealistically, to hear a report of Irma rapidly weakening or changing direction suddenly, that never comes. Others, find themselves staring at satellite images of the hellacious Hurricane; eyes glazed, faces white, hands wrung together. And all around them, the waters that had once been a warm and dreamy paradise, have manifested into a bloodthirsty medieval army, surrounding Barbuda like pincers, and drooling in anticipation for the impending invasion of which Irma was the supreme commander.

With disaster relief supplies mobilized, and emergency crews poised at the ready, there was little more Barbuda’s government officials could do other than hold their breath, and watch. As for the rest of us, we gaped at Irma’s fatal symmetry from a distance, pondering dreadfully if anyone on Barbuda was going to emerge from this Hurricane’s imminent, and surely brutal assault, unscathed.

By nightfall on September 5th, conditions on Barbuda were beginning to deteriorate. Irma started out the invasion slowly—a gentle exploring of the island’s terrain; a deceptive caressing of its curves, crevices, and topography; an eager probing of its strengths, and its weaknesses. This quickly escalated into a carnal, lascivious frenzy; a predatory scream of the Hurricane’s raging winds; an aggressive, and vicious pressing of cyclonic weight against the island. Immediately, leaves start to be torn from their parent branches, and thrown into the hysteria. Objects not tied down are sent scuttling, akin to manmade tumbleweeds. Roofing slats of sheet metal are pried up and tossed like broken-off razor blades.

But this is merely the beginning. As Barbuda sinks deeper into the convective swirl of Irma’s CDO, the dark environment on the ground gradually roars harder in fury. The golden lights of Codrington and the rest of the towns snap off, sealing the lid of blackness over the island. Barbuda, now untethered from the constructs of humanistic modernity and infrastructure, was floating at the mercy of nature’s wildest, most implacable of assailants.

When Barbuda began to receive bands closer to the core of the sustained, 180 mph eyewall of Hurricane Irma, all hell broke loose on the ground. Every tree on the island is suddenly shattered instantaneously; snapped like toothpicks off their trunks, or stripped of their leafy flesh down to the bone, by the teeth of a feeding frenzy of piranha-like wind gusts exceeding 200 mph. Roofs are torn away smoother than banana peels. Some structures are wiped off their foundations entirely, in scenes you’d usually only witness in an EF4+ tornado, somewhere in Kansas. A storm surge of at least 8 feet thrashes and pummels anything in close proximity to the beaches. A sensor records a wind gust of 160 mph before it fails (this same sensor also measures an atmospheric pressure of 916.1 millibars at sea-level). Soon, every single meteorological station on the island is destroyed. The conditions inside the eyewall become so extreme, that even many of Barbuda’s native animal species are under threat of having their precious habitats, reduced to unlivable spoilage.

I, myself, could only bear witness to the carnage across Barbuda through The Weather Channel’s coverage on the television, in the safety of my living room. But there was a deep, and mysterious wound that was piercing my conscious—a knife, twisted by Irma’s counterclockwise spin, in my side. While I could not direct any one of my five senses to know the esoteric terror the people on that tiny speck of land were currently going through, I had come across a radio station transmitting from the island, picked up by the reach of the internet, relaying live radio broadcasts from a variety of locales. At the time, I was searching desperately for any stream of information that was trickling out of Barbuda, as Irma’s scourging, western eyewall raked the isle—but what I found instead, was a moment that will never find its way out of the maze of corridors in my memory.

The radio station wasn’t broadcasting updates or information about the conditions on the ground… no, it was broadcasting music. And the reason this caught my attention, was because the songs being played weren’t indistinguishable songs—in fact, they were distinct hymns of prayer. Voices and lyrics crying out in hope, faith, and anguish, from the black depths of Irma’s treachery. I listened to these songs with a heavy heart, trying to comprehend the unprecedented, screaming winds that were tearing around this radio station… when, without warning, the music cut off abruptly, leaving only the hollow fuzz of static wafting through the air, like caustic smoke curling off the end of a cigarette. I exchanged a gravely dismayed glance with the nearest person to me, whom’d been listening to the radio as well; and it would be only minutes later when The Weather Channel returned from a commercial break, at just the moment when Barbuda’s silhouette emerged into the perfect calmness of Hurricane Irma’s eye.

Irma officially made landfall over Barbuda just after 1 am AST, September 6th, 2017, with record-breaking sustained winds of 180 mph (this was operationally notched at 185 mph, but was slightly reduced in post-season reanalysis). Were you to have been standing on Barbuda at this time—weaving your way through hopeless and hazardous tangles of tree branches, sheet metal, and lumber—you would’ve craned your head upwards, and gazed up through the hollow hole in Irma’s heart, at the brilliant sparkling of the clear, nighttime sky. And as you were bathed in this surreal, chilling starlight, you might’ve wondered how this pyrrhic pool of phlegmatic peace could possibly exist at the nucleus of a storm, containing such intense, and merciless violence.

This calm period in Irma’s large, cookie-cut eye was only temporary; and at 3 am AST, the other side of the Hurricane’s hell was upon Barbuda. If you can imagine bending a wooden popsicle stick—the ones you used in elementary school for shoddy and peculiar art projects—onto itself, this is akin to the impact that the first half of the eyewall’s fury had on Barbuda’s forests. The trees were torn, broken, and bent—but just as with the popsicle stick, you have to bend them the opposite way to fully sever their structure. This is what happened when Irma’s 180 mph sustained winds switched around 180°, blowing in the opposite direction for the entirety of the second half of the cyclone.

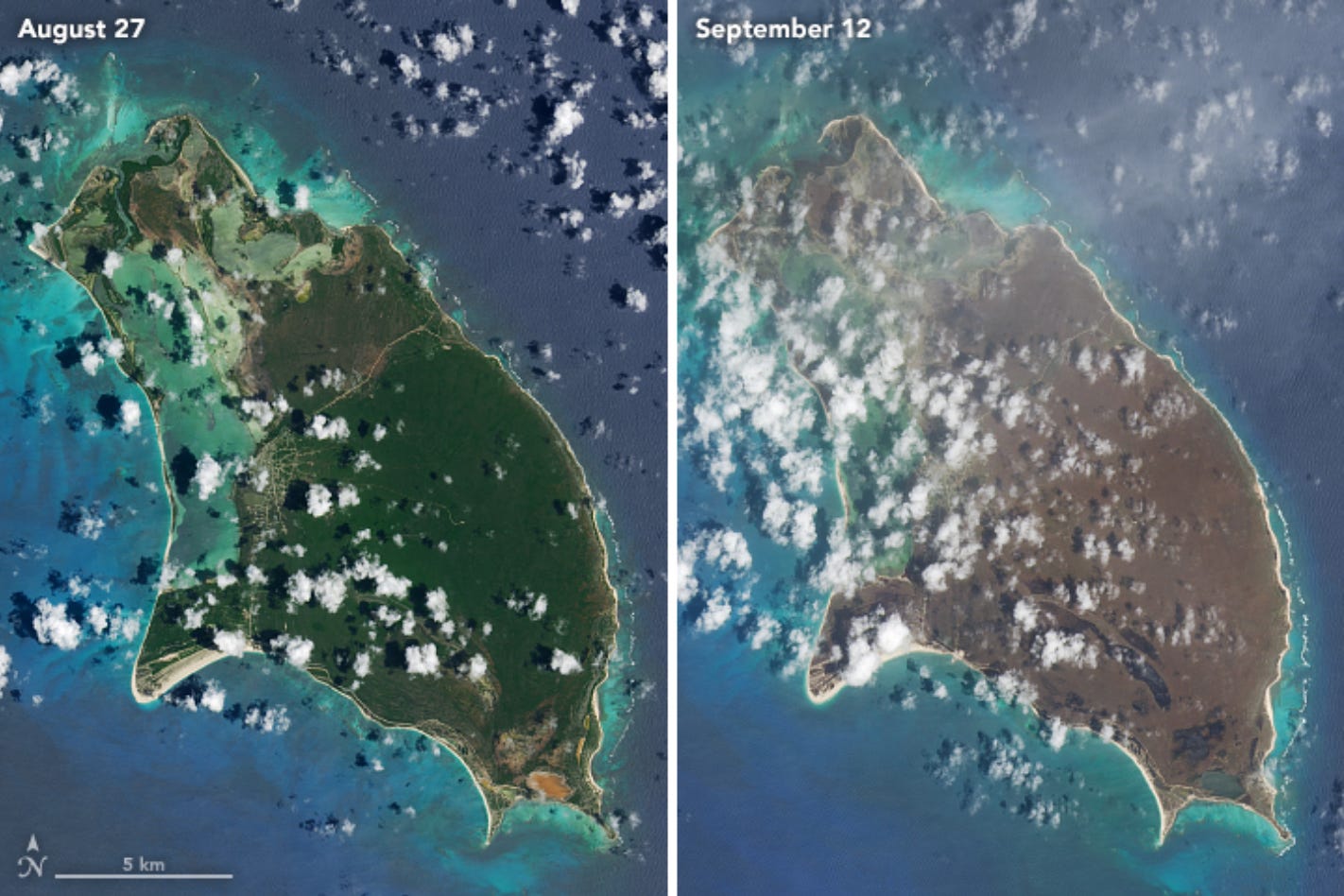

The eastern eyewall tears at Barbuda from the south, submerging the southern beaches that had initially escaped the push of the seawater surge. The woodlands and overall vegetation of the island are all but slaughtered; first cut by the butcher’s knife, and now tossed into the meat grinder—producing a wormy, mottled, and sloppymulch. Any manmade structures that had hung on to their integrity by a thread, are finished off with a final, killing blow. Massive mesocyclones arc out from the eyewall’s inner edge; and from above, the shudder of tropospheric gravity waves ripple across Irma’s frozen skin. The winds are a million freight trains that go on for miles… and their unstoppable momentum rampages across Barbuda, well into the night.

The First Domino Has Fallen.

By the 5 am AST NHC Advisory, Hurricane Irma was finally beginning to move away from Barbuda. The island remained trapped beneath heavy, tropical downpours for several more hours as the storm pulled off to the WNW—where Irma already had her sights set on which Caribbean havens she was going to butcher next.

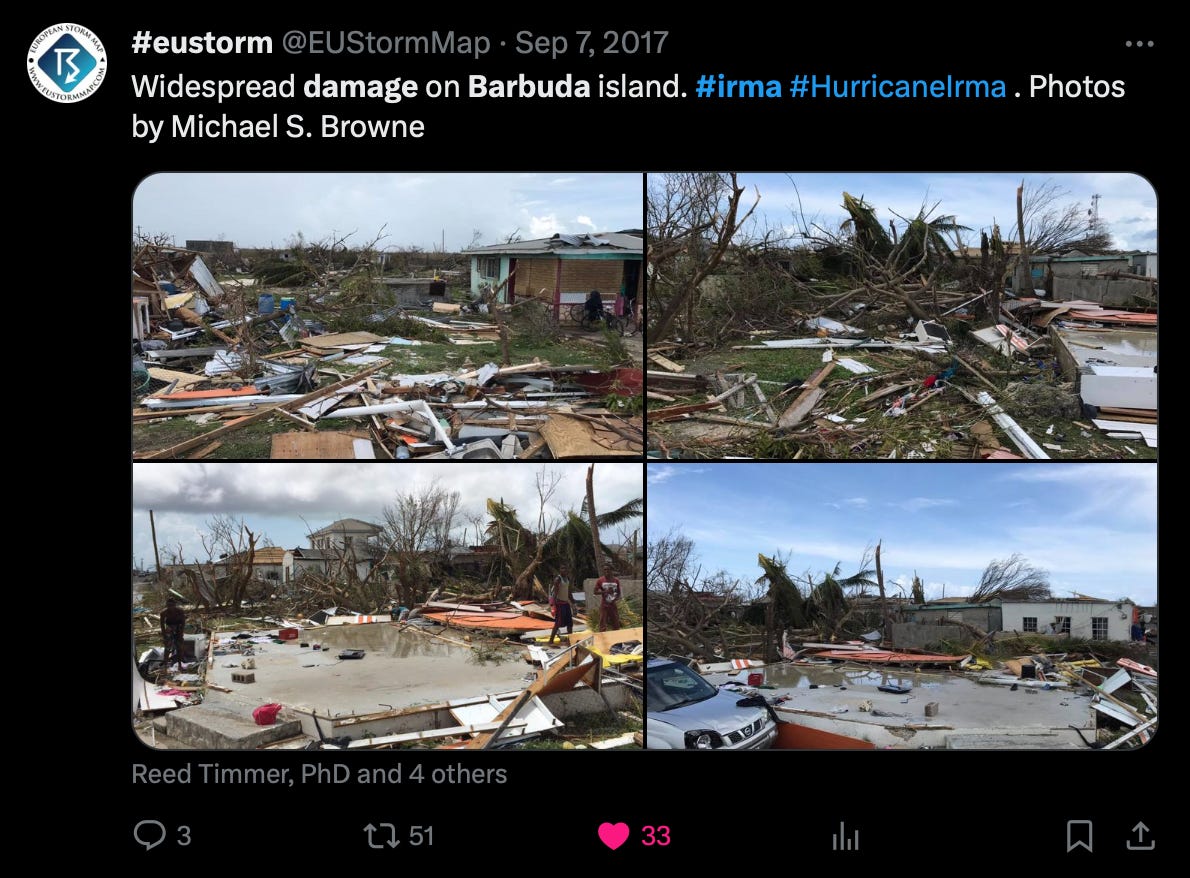

In the immediate hours following Irma’s first landfall, no one knew what fate had come for Barbuda. The island’s telecommunication infrastructure had been utterly devastated—and it seemed that no power line was left standing above the ground. With every facet of communication cleaved, the island’s existence could suddenly only be proved by seeing its physical presence embedded at the confluence of the Atlantic and the Caribbean.

Barbuda’s Prime Minister, Gaston Browne, surveyed the territory later that ruinous afternoon of September 6th, 2017. From this airborne view, Barbuda could’ve been mistaken for a war-torn atoll in the 1940s Pacific theatre. The entire island was completely stripped of its herbaceous tissue, leaving just the ghostly skeletons of broken and mangled trees behind. Cars were bashed, dented, and destroyed, the crystal-blue fragments of their window glass scattered around them. In just minutes of aerial survey, Browne concluded that Irma had either severely damaged, or destroyed, upwards of 95% of Barbuda’s buildings. This included the island’s sole airport, its two hotels, numerous schools, and handful of hospitals, among other facilities of basic infrastructure.

Some residential blocks were completely leveled. Others survived the Hurricane’s eyewall mostly intact (in part because of solid, concrete-wall construction) but were irreparably damaged nonetheless. Several more were gutted and cleaned out, left as hard, empty shells of what they used to be. Meanwhile, homes closer to the coast had suffered even worse damage, after becoming submerged in the 8+ foot tidal wave. The horrendous destruction was so evenly widespread, that it appeared as though Barbuda had always looked that way, with the memory of what it had looked like before feeling as old as the pyramids.

Overall, the totality of Irma’s catastrophic impact on Barbuda was gruesomely startling, and wholly unimaginable. All 62 square miles of the island’s body was transformed into the set of a Hollywood doomsday movie, in just a single night… and the harsh, guttural reality was that this was no movie, nor some twisted work of fiction. For the people of Barbuda, it may have initially seemed like a nightmarish fabrication of the morbid mind; but the realness, was nearly too painful to bear. For them, the disaster was only just beginning, as their entire homeland had just been rendered altogether uninhabitable. They tried to come to grips with the fact that they had just endured a storm of sincerely inconceivable extremes; a storm so rare, you could visit over 180 countries in the world, and not find a single person who could claim to have experienced a tropical cyclone of similar strength.

But hardly 48 hours after Irma’s catastrophic landfall, the wrecked and despoiled remains of Barbuda were already facing another war from the eastern horizon. Another storm… another Hurricane, freshly spawned by Africa’s west coast, was marauding across the MDR. Irma had left nothing and everything in her wake—the environment ahead of this new tempest was lush, favorable, and conducive. And standing amongst the endless piles of rubble—in a paradise-turned-hellscape, razed to the ground by a destructive force that did not discriminate against man nor nature—the inhabitants of Barbuda were now in the path of the rapidly intensifying Hurricane Jose. This storm, too, was pushing the envelope of the MDR’s historic intensity ceiling, and his winds had already rocketed to 155 mph—making him a high-end Category 4. With Hurricane Irma still cutting down island, after island, after island, to Barbuda’s west, there were now two 155+ mph Hurricanes simultaneously spinning in the Atlantic Ocean, for the first time in recorded history.

On September 8th, 2017—less than 2 days before the potential landfall of Hurricane Jose—a mandatory evacuation was ordered for the entire population of Barbuda… some ~1,800 people, whom were now roaming numbly through the wreckage of what had once been their home.

In the blink of an eye, there would be, for a time, no human life present on this tiny, Caribbean island.