Our relationship with the Earth is a tumultuous, sometimes tempestuous one; we are both captivated by her wonderfully imperfect beauty, and fearful of the temper with which she holds in the chambers of her fiery heart. Some days she brings us love, respect, unending comfort and happiness; while others, she screams in seemingly unreasonable tantrums of rage, becoming unpredictable, irrational—and even dangerous. To us, Earth feels black and white; fire and ice; a bittersweet chocolate that either melts in your mouth or leaves a terrible aftertaste in your throat; an enormous, molten magnet grudgingly crushed between her two poles inside a claustrophobic blue marble.

But if there ever were an example of one of Earth’s creations sauntering haughtily, confidently, and proudly through that daunting gray area we fear the most—that space between the lines; the chocolate whose flavor is perfectly balanced; that point at which the fire melts the ice at the same rate that the melted water extinguishes the fire—then Hurricane Isabel would be the quintessence.

Isabel—the name alone rolls off the tongue with an enchanting, seductive grace. It holds inside it both the syllables of pretty softness and divisive rigidity; undertones that drive you to excitement as much as they instill consternation. It was the name christened to the Queen of Cape Verde over the climax of 2003’s Atlantic Hurricane Season—when the volatile and vortical impulses of oceanic thunderstorms was at its hottest during that year. Over the course of two powerfully conflicting weeks, the storm with that beguiling name, pirouetted across the immense Atlantic oasis, building for herself a reputation of enticing vigor and venomously alluring toxicity. And with every hour that she twirled, she inched closer and closer to the millions of people who call the Mid-Atlantic coastline their home.

It was there, in the Carolinas and Virginias, the centers for some of America’s richest history and Southern folklore, that Isabel was coerced into running aground… it was there, where she sought to break hearts, and leave her proverbial lipstick mark on the U.S. Eastern Seaboard for years to come.

12 Days to Landfall—Journey from Cape Verde.

Coming into September, the 2003 Atlantic Hurricane season had been a relatively active one. Cyclogenesis had begun well ahead of the official start of the season, with Tropical Storm Ana coming into shape as early as April 20th. July saw the spawning of two Category 1 Hurricanes, Claudette and Danny, as well as two other systems that failed to achieve Tropical Storm status. In August, Hurricane Erika peaked with 75 mph right before making landfall just south of Brownsville, Texas, and on the month’s 28th day, Fabian was named a little over 420 miles west of the Cabo Verde islands.

Unlike the other Hurricanes up unto that point in the season, Fabian would go on to develop into a classic, Main-Development-Region (MDR) Major Atlantic Hurricane, becoming 2003’s first truly fearsome spinner. At his peak intensity on September 1st, he packed powerful winds of 145 mph, supported by a 939 millibar core pressure in his oblong but highly-defined eye—a solid, large, Category 4 beast. Five days later, Fabian’s eastern eyewall plowed through the island of Bermuda… a place that finds itself in the path of large Atlantic Hurricanes nearly every year, but is almost always spared due to the unlikely odds of a tropical cyclone happening to come within their tiny, <20 mile wide diameter. Fabian, however, said, “To hell with the odds!”, and became the first storm to strike a direct hit on the island since Hurricane Arlene in 1963.

Despite Fabian’s brisk 17 mph northward pace, Bermuda remained beneath his powerful eyewall for over 3 hours, as the storm’s massive, 115 mile-wide diameter of Hurricane-force winds prolonged the conditions on the ground. The eyewall itself was quite remarkable, having both its 1-minute and 10-minute sustained winds solidly whirling at 120 mph—an exceptionally rare consistency in strength. The highest gust recorded on the island was clocked at a whopping 164 mph (confirming Fabian’s Category 3 intensity), while an 11+ foot storm surge besieged coastal beaches and harbors. 20-30 foot waves also wreaked havoc in Bermuda’s immediate backyard, capsizing several vessels.

Hurricane Fabian caused the first ever Hurricane-inflicted fatality in Bermuda’s history (there would be 4 casualties total), and the storm would be the most damaging in the territory’s modern existence, vandalizing over $200 millions dollars worth of the island’s infrastructure. The damage was such that the name Fabian was permanently retired from the Atlantic Hurricane naming list.

So the 2003 Atlantic had already churned out a large, vintage, Cat 3+ MDR Hurricane by September 6th—thus, many hoped that Fabian would turn out to be the season’s so-called ‘Big One’. Unfortunately, the Cabo Verde thunderstorm train was far from pumping the breaks.

Back on September 1st, when Fabian was still roaring through the central Atlantic as a Category 4 Hurricane, a fresh tropical wave slid off the West African conveyor belt and splashed into the Eastern Atlantic. Already biting at Fabian’s heels, the loosely conglomerated area of interest initially encountered relatively hostile conditions. With dense layers of dry, Saharan dust in the immediate area south of the Cabo Verde islands, the fledgeling system became chapped and atrophied, as dust ate away at the disorganized seedlings of convective activity. But on September 5th, conditions dramatically improved, and the primal system made an unusual jump from her mundane classification as an ‘Area of Disinterest’, to a closed-low pressure system with healthily blooming convection. The system was upgraded to Tropical Depression Thirteen during the overnight hours of September 6th—and the unique rapidity of the early organization continued that morning, as just six hours after designation, Tropical Storm Isabel was born.

The highly conducive environment supported the aspiring Tropical Storm with earnest; sliding a curling iron into her developing banding features, the light wind shear and conducive instability inspired Isabel’s rainbands to coil inward towards her increasingly defined low pressure core. Thunderstorm activity continued to blossom, and an atypically large eye-like feature started to clear out near the center. By 11 am AST (Atlantic Standard Time) on November 7th, hardly 24 hours after receiving her name, Isabel was upgraded to a Category 1 Hurricane by the National Hurricane Center. Dvorak-technique satellite estimates analyzed the system to be sustaining winds of 75 mph, while the partially clouded eye had already sunk its pressure down to 987 millibars. At this time, the 2003 season’s 5th Hurricane was located 1,610 miles east of the Leeward Islands, far outside the reach of the Air Force’s Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance planes. Considering her extreme distance and travel time away from any landmasses, the NHC merely stated that Isabel was currently, “…NO THREAT TO ANY LAND AREAS…”, in their bulletin on the 7th, because forecast models were unable to determine how far west the Hurricane was ultimately going to meander.

While Fabian pulled north of Bermuda speedily, eroding as he tread over the north’s cooler waters, Isabel’s story was just beginning.

Early on, her intensification was steady, methodical, and organized. While moving almost due-northwesterly, Isabel was efficiently harvesting the warm, moist air of the Atlantic Ocean with the reap of her threshing winds. Convective updrafts excelled, linking arms and growing the storm in size. The CDO developed astutely in response, surrounding an impressive, 30+ mile-wide eye in Isabel’s center. Outflow patterns thrived exceptionally in the embosoming comfort of the deep tropics, being allowed to spread their wings and pull in deep, dreamy inhalations of oxygen into Isabel’s lungs. Exactly 24 hours after Isabel first reached Hurricane status, the NHC determined her to have attained 115 mph sustained winds, making her a Category 3 Major Hurricane. Upon the 11 pm AST Advisory, that strength had increased further still to 135 mph—giving Isabel Category 4 caliber winds. The core pressure had fallen to a neatly intense 948 millibars—dropping 14 millibars alone over the course of that afternoon on the 8th.

Isabel held this peak intensity for about a day, before the bullies of wind shear inevitably sauntered down the alleyway. Clipping the Hurricane’s eastern quadrant, the shear shoved, choked, and taunted Isabel’s outflow banding, leading to a constriction of air intake into the system’s core. Isabel’s eyewall coughed as a result of this; and like a cheetah prowling in the savannah brush, hungry to ambush a sick and lame piece of prey, the nearest convective rainband to the eyewall leaped from the grasses, seizing the storm’s ring of strongest winds in its jaws. The main eyewall warmed and shallowed with the sting of the bite, falling into and clouding the Hurricane’s bleary eye… but nevertheless, Isabel refused to panic. Her confidence was brimming; her vanity, overwhelming. She believed it credence that she was going to make herself into a sight of such magnificence, eloquence, and elegance, that those who laid their eyes on her would have their memories burned with the dazzling, smoothly rounded image of her invariable smile. It was just a matter of time.

7 Days to Landfall—”The Beauty and The Beast”.

Each sub-region of the Atlantic tropical basin owns its own notorious stereotype for the storms they develop—the breed of Hurricane they spawn, if you will. Whether you’re discussing the tendencies of the northeastern Atlantic to produce weak, looping cyclones, or the Caribbean Sea’s urge to explosively intensify tight, octane-crazed Category 5s, it’s a distinction that follows real trends in storms’ appearances, nature, and demeanor. And perhaps the most infamous of all sub-basins is the Main Development Region of the central Atlantic: creator of the romantically fabled Cape Verde-type Hurricanes.

But just what makes these storms shine so brightly in the light of the weather paparazzi? There are several important factors that come together in the birth of Cape Verdes that shape and mold them into that classic, symmetrical buzzsaw that first comes to mind when our ears first hear the word, ‘Hurricane’. They combine to make these storms contain the greatest potential for extreme destruction to threatened coastlines in the entirety of the Atlantic Basin. The variety of reasons for this are as follows:

- As mentioned previously, Cape Verde Hurricanes can be enormous. Their origins as broad tropical waves, their unlimited oceanic real estate, and their typically very long periods of time over water (meaning that they will endure repeated Eyewall-Replacement-Cycles—EWRCs—over their lifetime, with each cycle temporarily weakening the storm and therefore incrementally increasing the radius of gale-force winds), often expands the Cape Verdes to truly massive sizes. Larger Hurricanes = greater storm surge potential, as well as a wider swath of areas impacted. This also negates the interpreted “positive” effects of weakening prior to landfall (which Cape Verde storms almost always do), as the Hurricane’s magnitude becomes more relevant than its peak wind strength.

- The open Atlantic may not contain the flash powder oceanic heat content that the Caribbean or Gulf of Mexico have, but its deep, tropical waters are still plenty warm enough to fuel some of the hungriest Major Hurricanes to ever roam the basin. And because of the near-endless road of heat energy ahead of them (along with the lack of any hostile landmasses for hundreds of miles in any direction), Cape Verde Hurricanes have free reign to intensify as much as their eyewalls desire (within the intensity ceiling of the heat content). Equally important is the duration at which they can hold their high intensities, again due to the vast expanse of the open ocean, in addition to their size (since larger storms are much less volatile and prone to radical rises/falls in strength).

- Finally, it’s that same, iniquitous privilege of swimming in the salty soup for days upon days, sometimes even weeks, that empowers Cape Verde Hurricanes to collect, scoop, and accumulate a voluminous mass of seawater beneath them. Once squeezed into the shallow coastal depths, the water has nowhere to go except to spill over beach dunes and inundate dozens of miles of beachfront real estate.

So the danger of MDR Hurricanes is well understood—the only question that remains is which path they choose to take down the yellow wave road. And this isn’t a straight forward problem for forecasters and global model algorithms to solve. The environment that dictates the direction of Cape Verde Hurricanes is a finicky, dynamic setting of rapidly evolving currents and steering flows. It revolves around the strength of a high pressure ridge in the north-central Atlantic, colloquially referred to as the Bermuda High. This high pressure steering current fluctuates in strength over the course of every Hurricane season, and this is what determines whether the long-tracking MDR systems make it to the Caribbean Islands/continental United States, or curve away beforehand. The stronger the ridging, the more a system is blocked to the north, thereby forcing the storm to travel more westward, where land impacts will begin to come into play. A weaker ridge, on the other hand, acts as a courteous valet chauffeur, politely opening the door for storms to escape out and away to the north, which is their natural inclination.

The strength of the ridging is dependent upon an extremely complex climatological interaction of jet streams, troughs, and other low-pressure systems, to name a few… however, the vast majority of the time, the ridging trends weak, leading to nearly nine out of ten named storms, borne from the Cape Verde wave train, curving harmlessly out to sea. This was the case with Fabian in August-September of 2003—he just happened to run into Bermuda along the way.

But by the time Isabel was next in line for the spinning carousel ride west, the situation had changed dramatically since Fabian’s passing. The high pressure ridging had built back sternly, shutting the door in Isabel’s face and throwing away the key. She probed her side of that door during the morning of September the 10th; whispering softly with the wisps of her cirrus outflow bands to the Bermuda High to let her through, to allow her to frolic in the icy Paradise of the tropical afterlife in the cold oceans of the north. But the High would not listen—resolute and dogged, it stubbornly refused Isabel her requested passport to the Arctic Circle.

Discouraged, spurned, and resentful, Isabel suddenly seethed with a new purpose. She had been denied the road that she so desired… now, she saw no reason to glaze over—to hide, conceal, and diminish—who she truly was, any longer.

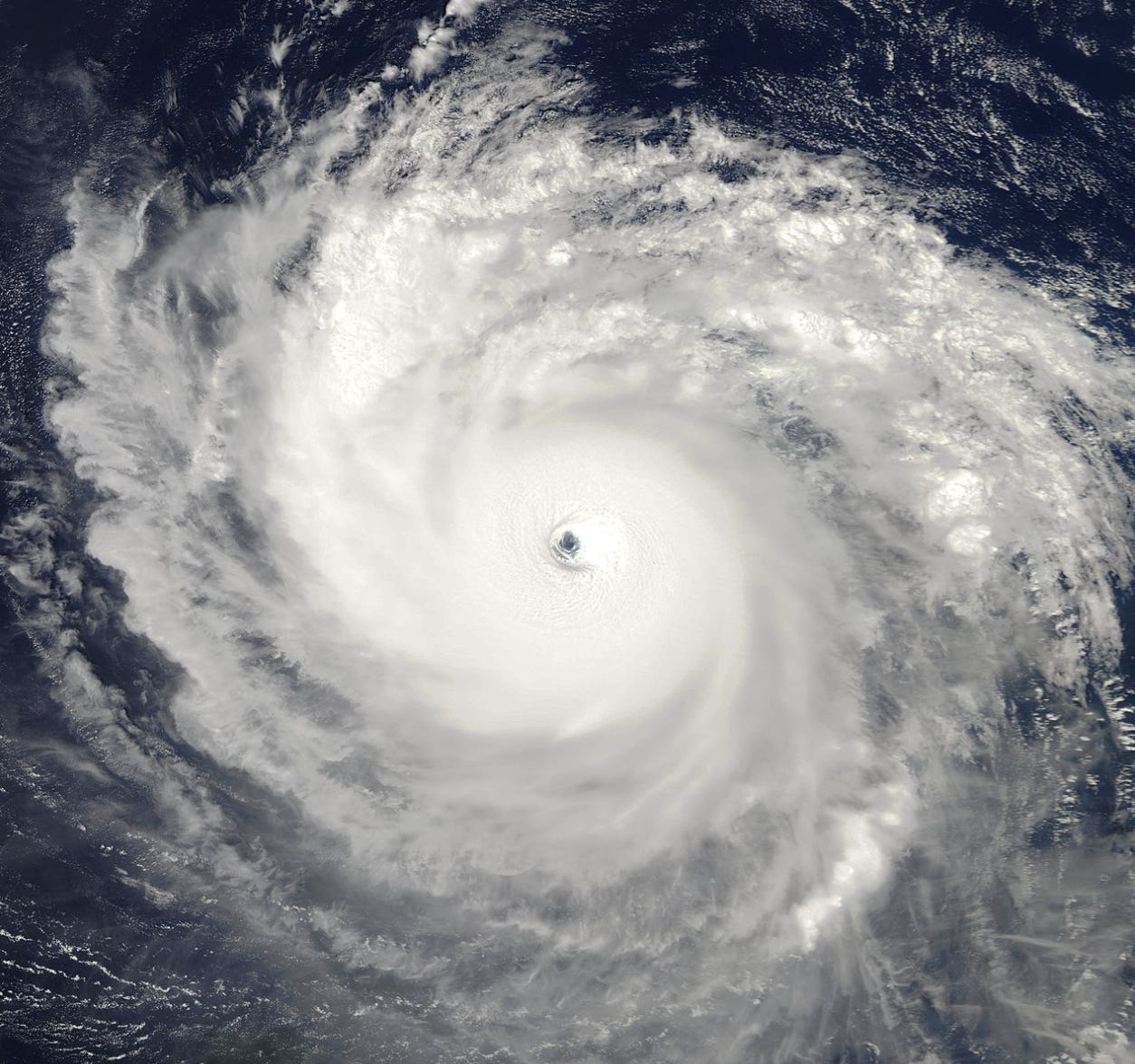

On September 11th, 2003—the second anniversary of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centers—Hurricane Isabel’s bosom swelled as she took in a boundless breath of energizing air. The secondary eyewall set like a fast-drying super glue, and her convection deepened with equal eminence to her respiration. Her clouds were the color of frosted cream; her eye, a deep pool of swirling, cerulean mystery. The captivation of her pure beauty, and the entrancing dance of the mesovortices within her being, seduced you astray from the raw violence with which she pleaded. The National Hurricane Center referred to her appearance as ‘textbook’… but this word did not do justice to how gorgeous Isabel had become.

Beginning a second phase of rapid intensification overnight through the 10th, Isabel officially became a Category 5 Hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Scale upon the 4 pm CDT NHC Advisory, packing 165 mph sustained winds, and a very deep core intensity of 915 millibars—making her, at the time, the strongest storm ever observed outside of the Caribbean/Gulf of Mexico by both wind speed and pressure. Isabel had fulfilled her passionate goal of magnificence—and burn the memories of her gaping observers, she did. Her strength was unprecedented, so too her glamor. She was the twirling epitome of everything that was to be envied; her slow-motion spin turned heads, and glued eyes. She was basking in the glory of perfection—a validation greater than staring herself in the mirror, for she knew exactly how “textbook”… no, attractive, of a natural phenomenon she really was. She was endowed with both winsomeness and rage; every piece and curve of her anatomy—the eye, the eyewall and CDO, the rainbands and outflow channels, the tropospheric influx and heat exchange rates—all of it, was absolutely flawless.

~1,532 miles west of where Hurricane Isabel was swaying to the dizzying and dreamy beat of the Coriolis song, forecasters at the National Hurricane Center were growing apprehensive. By now, it was clear that the Atlantic ridging was going to be too strong to allow Isabel solace in the north before Bermuda’s longitude—and the U.S. east coast, as a result, fell into the potential crosshairs. But with a possible landfall still a week away, trying to discern anything from the forecast models grasping out that far, would be like trusting the word of the wolf when he assures he’ll only eat the sheep outside of the farmer’s fence. As noted in the 4 pm advisory:

“THE BIG QUESTION CONTINUES TO BE WHAT WILL HAPPEN BEYOND THE 5-DAY FORECAST PERIOD. IT IS STILL IMPOSSIBLE TO STATE WITH ANY CONFIDENCE WHETHER A SPECIFIC AREA ALONG THE U.S. COAST WILL BE IMPACTED BY ISABEL. THIS WILL LIKELY DEPEND ON THE RELATIVE STRENGTH AND POSITIONING OF A MID-TROPOSPHERIC RIDGE NEAR THE EAST

COAST AND A MID-LATITUDE TROUGH TO THE WEST OR NORTHWEST AROUND THE MIDDLE OF NEXT WEEK. UNFORTUNATELY…WE HAVE LITTLE SKILL IN PREDICTING THE EVOLUTION OF STEERING FEATURES AT THESE LONG RANGES.”

-Forecaster Pasch

On the afternoon of the following day—September 12th—the first Air Force reconnaissance mission into Isabel arrived, reporting back maximum sustained winds in the outstanding eyewall pattern of 160 mph—confirming the satellite estimates from earlier. They also found a minimum pressure of 920 millibars as they flew through Isabel’s eye, again adding confidence in the Dvorak-technique’s conclusions. By this time, Isabel was moving steadily west at 9 mph, growing in size to 185 miles across. Microwave imagery revealed the development of another secondary eyewall was well underway within Isabel’s CDO—this was nothing unexpected for an MDR Major Hurricane, as they faithfully fluctuate up and down in intensity due to natural cyclonic processes. After holding Category 5 intensity for ~30 consecutive hours, Isabel finally dropped back down below ~157 mph at the 4 am CDT November 13th NHC Advisory. A further Hurricane Hunter mission verified this data, while also recording the presence of two concentric eyewalls inside Isabel’s clamorous inner dynamics. The ongoing EWRC would complete later that day (on the 13th), signaled by the re-cooling of the storm’s eyewall cloud tops, and the clearing of an even larger, 40 mile-wide eye.

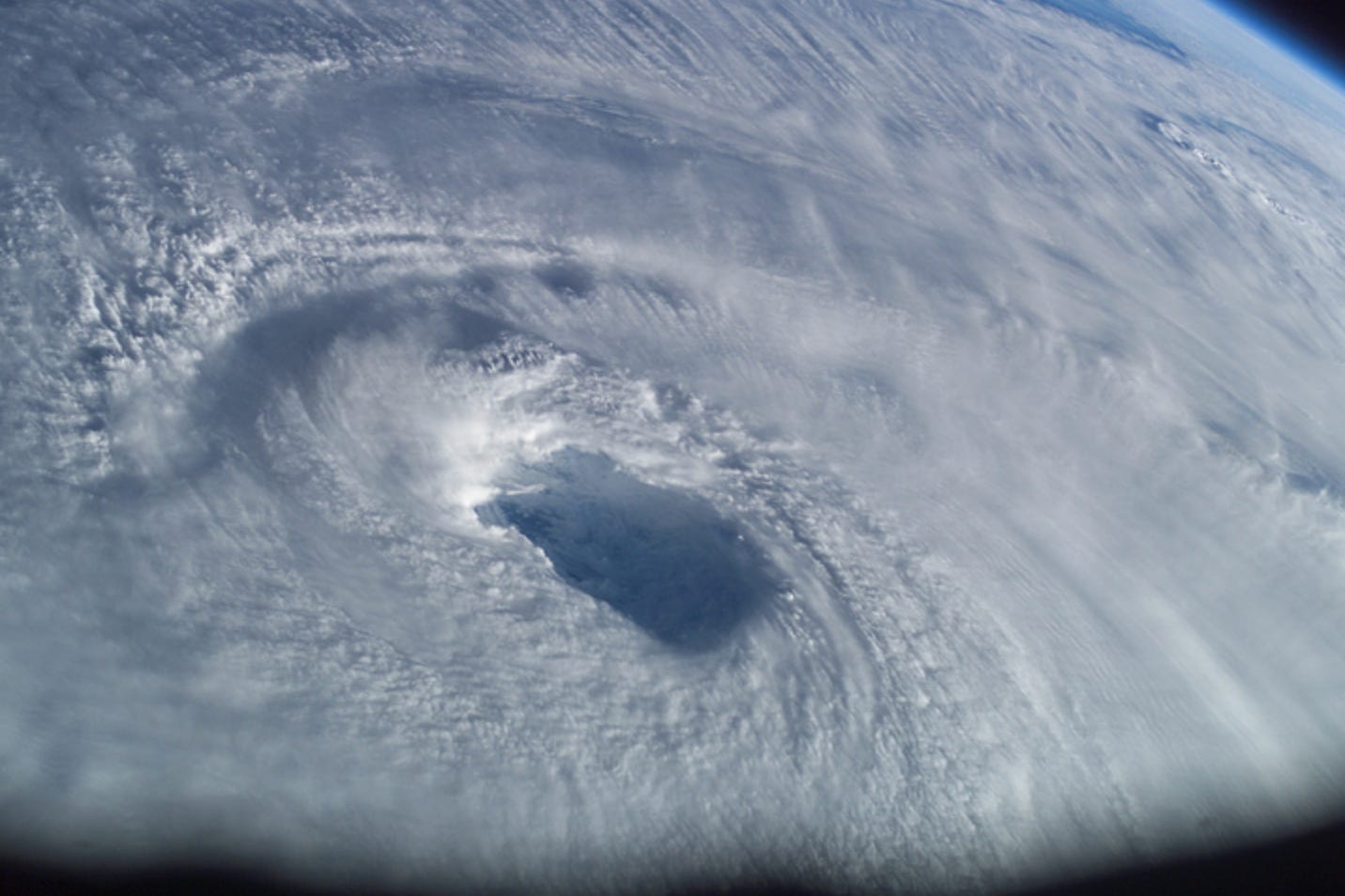

Hurricane Isabel briefly re-attained Category 5 intensity later that night, and under the control of the third eyewall in her lifetime, she was transformed into one of the most unforgettable, gorgeous sights you will ever lay your eyes upon in nature. Showing off with a monumentally massive pinwheel eye—surrounded by a perfect, doughnut-like CDO—Isabel became a rare annular Hurricane (a tropical cyclone that lacks any distinct rainbands around its periphery, hence featuring just a single ring of thick convection around its typically above-averaged size eye) on September 14th, while spinning roughly ~350 miles north of Puerto Rico.

It was during this third peak intensity phase that a Hurricane Hunter dropsonde, descending inside Isabel’s eyewall, recorded an instantaneous wind gust of 233 mph—the fastest gust ever recorded inside an Atlantic Hurricane in history.

It proved, if nothing else, that Isabel was churning with one of the most fiery motivations that could possibly be expected of a storm—if that wasn’t already clear enough based on her superficial image alone. She was a truly spectacular beast.

“THE EYE REMAINS VERY DISTINCT AND CIRCULAR…ALBEIT WITH AN UNUSUALLY LARGE 40 NMI DIAMETER. THE INTENSITY HAS ONLY BEEN DECREASED SLIGHTLY DOWN TO 135 KT SINCE THE EYE HAS BECOME EMBEDDED DIRECTLY IN THE CENTER OF THE CENTRAL DEEP CONVECTION. SUCH PERFECT SYMMETRY OFTENTIMES INDICATES A CYCLONE STRONGER THAN SATELLITE THE ESTIMATES…”

-Forecaster Stewart

But at the time of the 10 am CDT Advisory on November 14th, less focus was being directed towards Isabel’s strength, and instead shifted to her predicted track:

“THERE WAS A SLIGHT WESTWARD SHIFT TO THE MODEL CONSENSUS…BUT THERE IS NOW MUCH LESS DIVERGENCE AMONG THE GLOBAL AND REGIONAL MODELS THROUGHOUT THE FORECAST PERIOD. UNFORTUNATELY…THE MODELS ARE NOW IN EXCELLENT AGREEMENT WITH ISABEL MAKING LANDFALL ALONG THE CENTRAL U.S. EAST COAST IN ABOUT 4 DAYS.”

-Forecaster Stewart

Satellite position fixes on Isabel’s location were coming into agreement, with the latest coordinates designated by model runs earlier that morning—indicating a U.S. landfall was likely with a high-degree of confidence.

North Carolina now found themselves holding the red cape in front of the beast’s eyes. With every hour that passed, the Cape Verde beauty who called herself that candy-sweet name of Isabel rolled closer and closer to the Outer Banks.

3 Days to Landfall—Going All the Way.

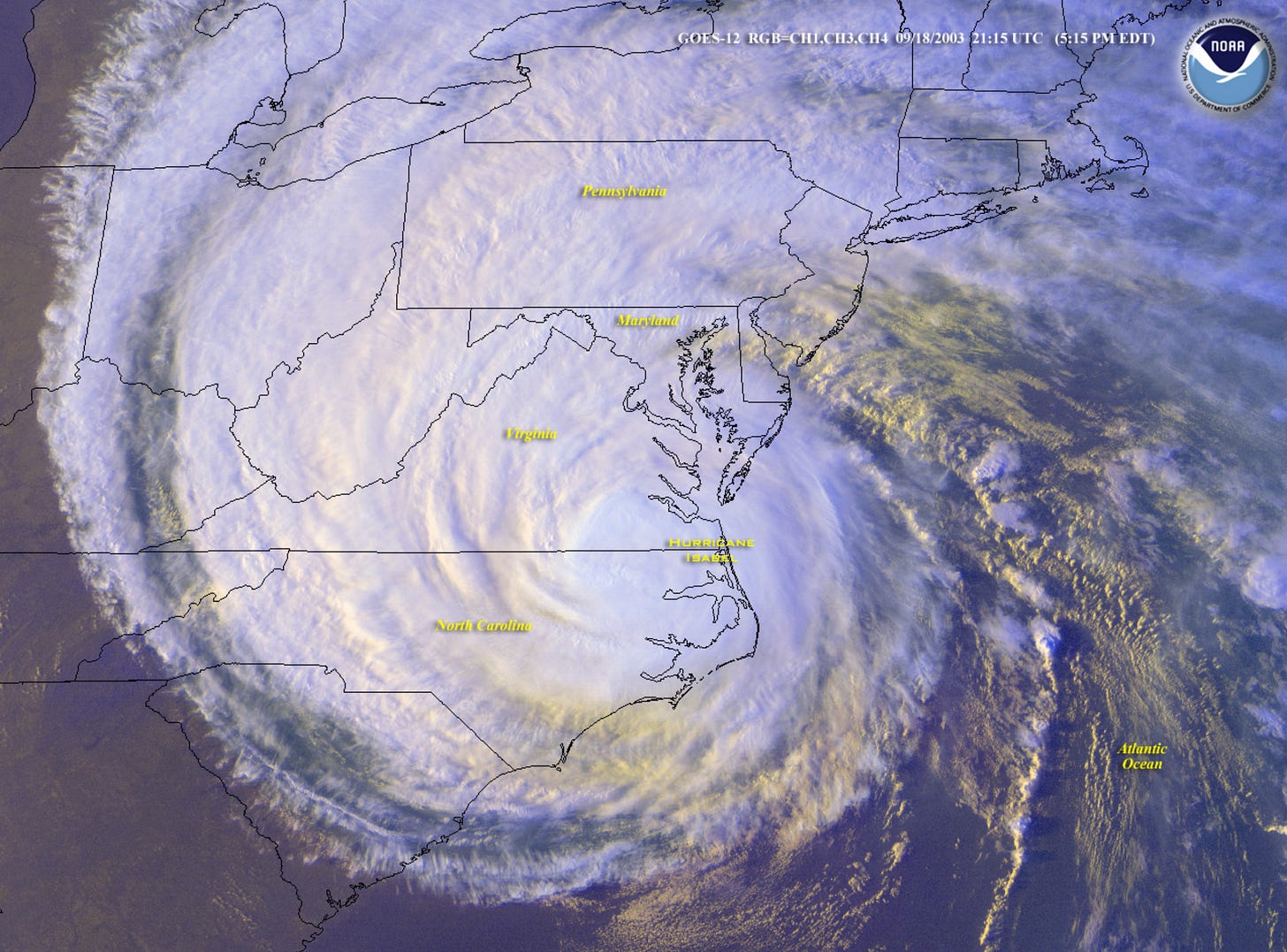

The countdown was now underway for the U.S. East coast, as there was no longer any doubt Hurricane Isabel would be rounding third base… and the mid-Atlantic states of North Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and Maryland, represented home plate. Preparations were initiated hurriedly, while forecast guidance, three days out from impact, was predicting an exceptionally frightening scenario for Isabel to make landfall in the Outer Banks as a massive, Category 4 tempest. This conclusion was drawn from the favorable jet stream interaction to Isabel’s north (enhancing outflow in that quadrant), and the anticipation that the storm would be moving over the supercharged underwater current known as the Gulf Stream (which parallels the eastern seaboard up until Virginia). This was not without precedent, as the Gulf Stream had kicked its spurs into several Major Cape Verde Hurricanes in the past, right before they made landfall in the U.S.—the most notorious example was Hurricane Hugo in 1989, who suddenly and rapidly intensified into a 140 mph Category 4 (after having weakened well below Major Hurricane status) in the last few hours before he struck South Carolina with a catastrophic, 20+ foot storm surge. Forecasters feared Isabel would take a smilier course of action—only this time, not just in a single port city (Charleston, SC), but in a densely populated complex of major urban areas and low-lying inlets, anywhere from Norfolk, Virginia to Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Meanwhile, 780 miles south-southeast of Cape Hatteras, NC, Isabel’s westward amble was slowing in preparation for a turn to the northwest—the final sprint to the finish line. 250 miles above the storm that day, the newly completed International Space Station passed over Isabel’s pretty face. Astronaut Ed Lu was there to capture the breathlessness of the Hurricane’s cloud patterns, shooting several, incredible photographs with a 180 mm digital camera through the space station’s windows. The pass on the 15th was actually the second time Lu captured Isabel’s ravishing cloud structure in such remarkable detail—the first came on September 13th, while the storm was a high-end Category 4:

In extraordinary detail, Lu’s photos encapsulated the wild, untamed, and sensational aesthetic mechanics of Isabel’s eyewall. It was due to the Hurricane’s ridiculously larger-than-normal eye, that the terraced stadium effect and mystically swirling mesovortices, could be seen in such finite detail.

Isabel’s florid fourth peak intensity on September 14th, as an annular-shaped Category 5, would be the third and final time she reached the maximum intensity on the Saffir-Simpson wind scale—cumulatively, she spent ~42 hours as a Category 5 over her lifespan. Her weakening was only slight, however, and Isabel remained an impeccable Category 4 monster through September 15th… and at that time, little change in intensity before landfall was expected.

Back in the U.S., mandatory evacuations went up for 24 different counties across Virginia, North Carolina, and Maryland. Dozens of train lines, schools, and airports were closed up and down the eastern seaboard, while people flocked to hardware stores in search of prescient supplies to resist Isabel’s anticipated fury. The United States Navy evacuated nearly all of their ships, submarines, and aircraft from Naval Station Norfolk. In Canada, national media coverage of Isabel was nearly as extensive as in the U.S., when meteorologists there warned that the storm may inflict the worst cyclonic impacts in the country since Hurricane Hazel’s devastating flash flooding in the city of Toronto, in 1954.

In spite of the evacuation orders issued for the Mid-Atlantic states (facing their first Major Hurricane impact since Floyd’s glancing blow four years previous), few people heeded the warnings seriously. In the Outer Banks of North Carolina, less than half of the local residents actually fled—while in the coastal counties of Virginia and Maryland, the evacuation rates were less than 25%.

On the other hand, however, there may have been a reason these evacuation rates were so low. Remember, the NHC anticipated only a slight, gradual trend of weakening during the next 3 days (up to landfall) for Isabel after she fell below Category 5 intensity that final time on September 15th. But undercutting that forecast was a sudden warming of the Hurricane’s cloud tops very late on the 15th, which hinted to forecasters that Isabel may be weakening more rapidly than expected. When analysts dug deeper into the forensics, they indeed noticed that Isabel seemed to be ensnared in a hidden bear trap of westerly, vertical wind shear, which hadn’t been anticipated by model guidance. The shear quickly made its teeth felt by deteriorating the storm’s neatly stacked cloud structure, ruffling the eyewall and degrading the eye’s cleanliness. By the morning of September 6th, the NHC reported:

“SATELLITE IMAGERY AND AIR FORCE RESERVE HURRICANE HUNTER DATA INDICATE THAT ISABEL HAS BECOME QUITE DISORGANIZED DURING THE PAST 6-12 HR. CENTER FIXES FROM IR IMAGERY ARE 20-25 NM EAST OF THE FIXES FROM THE AIR FORCE RESERVE HURRICANE HUNTER AIRCRAFT AND MICROWAVE DATA…SUGGESTING WESTERLY SHEAR IS AFFECTING THE SYSTEM. THE AIRCRAFT REPORTS THAT THE WIND FIELD HAS SPREAD OUT…WITH AN INNER RADIUS OF MAXIMUM WIND OF 40 NM AND SEVERAL MAXIMA PRESENT

OUTSIDE OF THAT. THE MAXIMUM FLIGHT-LEVEL WINDS HAVE BEEN 101 KT…AND THE LATEST CENTRAL PRESSURE IS 956 MB. THE MAXIMUM WINDS ARE REDUCED TO 100 KT…AND THIS IS LIKELY GENEROUS.”

Forecaster Beven

So, Hurricane Isabel, as it turned out, would not be a Category 4 Hurricane at landfall—nor a Major Hurricane in general. She had pushed and exercised every last means at her disposal to maintain her beautiful facade—now, once and for all, her appearance was eroding in the face of wind shear and cold-water upwelling. Jumping on the storm’s newfound weakness, an army of prowling rainbands ambushed the suddenly weakened primary eyewall, jostling each other roughly for a chance at Isabel’s heart, and in doing so inciting a chaotic erosion of the inner dynamics that did nothing but help the shear achieve its own, sabotaging goals. As the morning sun that day rose and warmed Isabel’s body, she had changed substantially overnight: the perfect eye, the frigid CDO, the envious outflow structure, was no longer. She now looked more reminiscent of a swirling lollipop, consisting of sweet-toothed memories and grand old times not that long ago.

So Isabel’s heyday was officially over—but her life’s mission, was not. The overarching fact that mitigated the effect of the weakening trend (which would continue up until landfall) had on Isabel’s potential severity, was her gargantuan radius of gale-force winds. The Hurricane’s size meant a dangerous quantity of fresh rain and salty seawater would roil its way to a U.S. landfall, regardless of the storm’s winds.

Maybe Isabel never did intend to wreak havoc on the U.S. coastline… perhaps that idea never really flipped her switch. But the ridging to the north had left her no choice. Now, there would be a landfall in the continental United States. And if that’s the way things had to be, then Isabel was going to make for certain—with the same passionate ambition that drove her to make herself in the image of irresistible cyclonic perfection—that her impact, her name, would be drawn in the wet concrete of the Atlantic’s history books…

Permanently.

The Clock Strikes Landfall.

North Carolina was among the earliest states in the United States of America. One of the first colonies to informally declare independence from Great Britain in 1775 (and, one of the first to secede to the Confederacy during the Civil War in 1861), North Carolina is about as north as you can go where people are still selling locally grown molasses straight out of their houses. From the harsh topography of the Smoky Mountains in the state’s west, to the low-lying marshlands of the Outer Banks in the east, the bigger twin of the Carolinas is a place of incredibly diverse biomes of wildlife and colorful contrasting human histories. It’s annual weather can be considered fairly mild and nondescript… except, of course, for the occasional summertime cyclone.

North Carolina is in a unique position on the U.S. coastline in relation to Cape Verde Hurricanes. Because the state’s thick, eastern 1/3 juts out in relation to the rest of the East Coast (for example, traveling due south from Hatteras Island—NC’s easternmost point—would put you about 250 miles to the east of Miami, Florida’s latitude), the risk for glancing strikes from recurving Cape Verde storms is exponentially higher in comparison to the surrounding states of Georgia, South Carolina, Virginia, and lower New England. As a result, North Carolina has experienced many, damaging tropical cyclones throughout their modern history—in fact, the most recent (and arguably the most significant) storm the state had weathered predated 2003 by just 4 years, when Hurricane Floyd impacted on September 16th, 1999 as one of the largest landfalling Atlantic Hurricanes ever recorded, killing 51 Carolinian residents and inflicting over $3 billion in damages.

Meanwhile, bordering North Carolina to the north is Virginia, a state that walks the line of being the preppy big city New England kid with a black leather jacket, and the old-fashioned Southern man wiping his blue-collar hands on his dirty overalls. As we considered above, Virginia has a much less storied history involving direct landfalls from tropical cyclones; most storms on the state’s registered tropical offenders were weakening systems passing by, who’d made landfall hundreds of miles away in other, distant states (Gulf Coast states, for example).

But residing on Virginia’s Atlantic side lies some of the most Hurricane-vulnerable coastline in the United States of America: the Potomac Tidal Basin. This cobweb of tiny rivers, inlets, and tidal streams—all stemming from the Chesapeake Bay hive Queen—closely infiltrates the environment, encompassing major, metropolitan cities such as Norfolk, Hampton, Annapolis, Baltimore, and even Washington D.C. itself.

Very few storms have ever made landfall into the Potomac Tidal Basin; and the ones who have made landfall near the area, almost always did so with touching swipes to the east. Most of the select minority of Cape Verde Hurricanes that impact the U.S. East Coast (outside of Florida, naturally), do so with landfalls in the Carolinas from the south, usually never getting their strong cores close enough to Virginia’s coast (which would require a more perpendicular strike from the east) as to block meaningful amounts of exiting river water in the arteries of the Potomac, York, and James Rivers. But Isabel was on the verge of bucking that status quo.

Hurricane Warnings came up 36 hours before landfall, extending everywhere from Cape Fear, North Carolina to Chincoteague, Virginia. All remaining voluntary evacuations in North Carolina were upgraded to mandatory—still, few left their homes. In the 80 mile-long lagoon of Pamlico Sound alone, 77% of residents chose to stay on the sandy atolls, despite having a 9 foot storm surge predicted for their respective locations. But the decisions were not entirely based on factors in their control: evacuation routes, as designated by state officials, were poorly planned and consequently, became highly congested as Isabel neared.

15 hours to landfall, and the Hurricane’s rainbands reached the Outer Banks—ground zero for Isabel’s grandeur. Conditions quickly deteriorated as a gray wall of water and wind swept off the raging Atlantic, announcing the trumpets of arrival for the storm that had been gradually making her way to landfall for a pain-staking 12 days. For hundreds of miles of U.S. coastline, Isabel’s swells battered beaches with wave heights consistently cresting 10 feet. As far south as Boynton Beach, Florida—a city a few miles north of Fort Lauderdale—the sea was raucous enough to capsize a boat and severely injure its two passengers. With hungry munches, Isabel ate away at the Eastern Seaboard’s beaches, eroding their away their sand and dune structures.

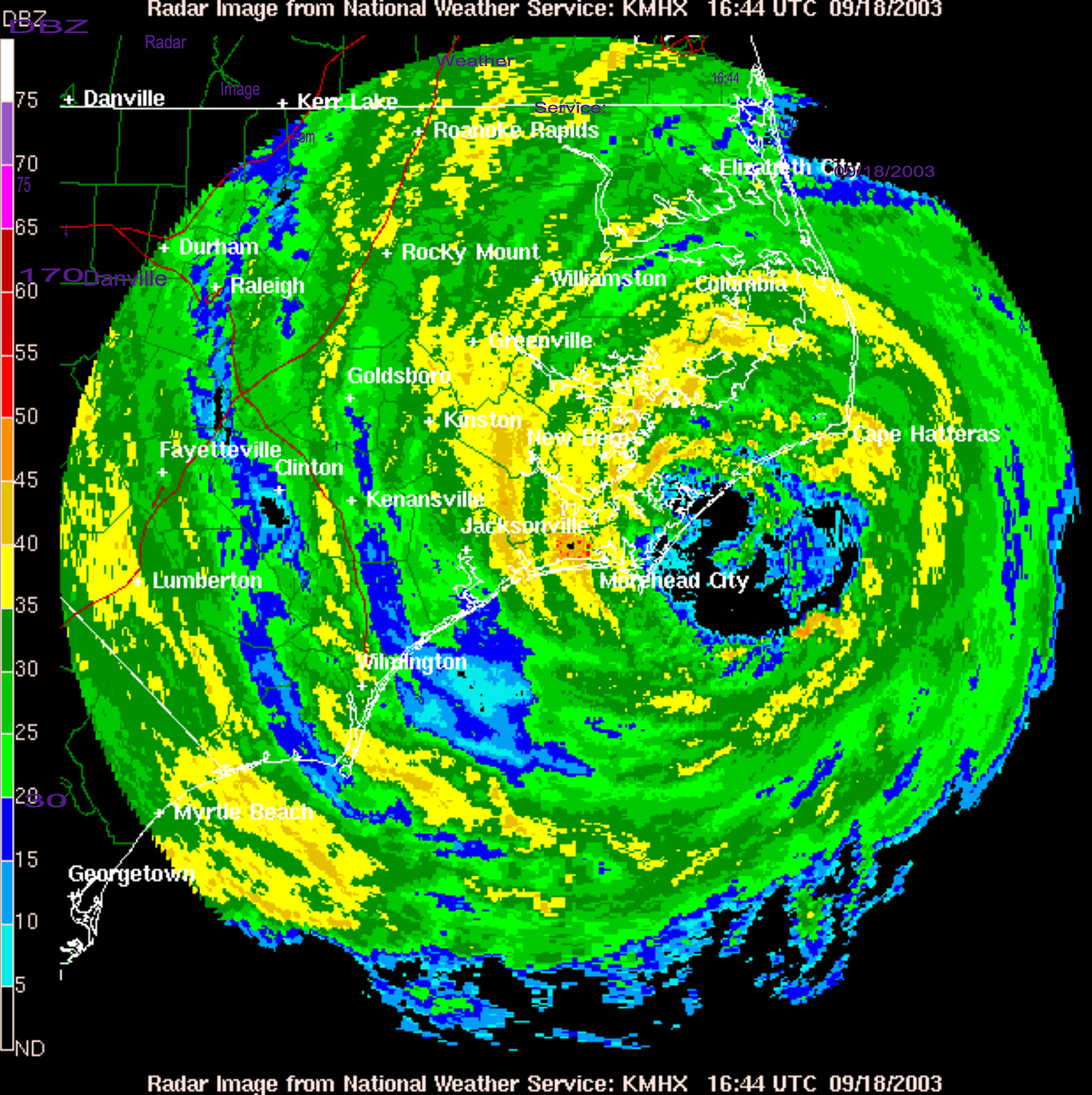

As Isabel’s eyewall neared, the Outer Banks descended into madness. Waves up to 25 feet in height chopped the hundreds of islands and lagoons into marshy pieces. Storm surge swept over the low-lying keys, reaching a heigh of 7.7 feet above normally dry ground in Cape Hatteras before the gauge was destroyed. On Ocracoke Island, residents waded through waters waist-high, fleeing for higher ground or houses on stilts while wind gusts over ~100 mph whipped through the town of Ocracoke itself. Powerful underwater currents lurked in seclusion from the naked eye, carving out breaches in barrier islands and washing out lengthy sections of North Carolina Highway 12. The largest of these breaches was a disastrous, 2,000 foot breakthrough in the middle of Hatteras Island. A three-pronged attack of Isabel’s ocean currents ripped gashes through the island up to 15 feet in depth, and in doing so washed out critical ground infrastructure such as power lines and water plumbing. Three houses (out of the ~40 that would be fully decimated in the Outer Banks) were caught on top of the developing chasm, and were completely destroyed by the surge. To this day, the massive, bleeding breach through Hatteras Island has become known by the vernacular name of Isabel Inlet.

Through the entirety of September 18th’s morning, the Isabel’s angry lashing was palpable. In a particularly terrifying anecdote, two families were reportedly caught swimming in the choppy floodwaters at the height of the storm, after their homes were knocked somewhat effortlessly from their pilings. Miraculously, the families managed to swim to higher ground, avoiding being drowned at sea and keeping Isabel’s death toll in the Outer Banks to a very fortunate zero.

The 345 mile-wide Hurricane Isabel officially made her long-awaited landfall around 12 pm CDT on September 18th, 2003, near Ocracoke Island, North Carolina. Her winds were (at most) sustained around 105 mph, and the pressure within her gargantuan eye was recorded at 957 millibars.

In the town of Oriental, within that trouble-minded Pamlico County, Isabel’s storm surge was much more furious than in most of the Outer Banks. Survivors described the surge as a 3-5 foot, rapidly charging tsunami of seawater rushing into the town, floating vehicles, toppling trailers, and lifting small homes from their foundations in just a matter of seconds. Elsewhere, in Albermale Sound, storm surge flooding also reached a height of 5-8 feet, causing significant damage to structures near the beaches.

Moving inland, the broadness of Isabel’s coruscation now came into effect. Sustained winds of tropical storm-force were reported as far west as Lumberton, NC—170+ miles away from the Hurricane’s landfall coordinates.

Even though Isabel was racing ashore at a speedy 18 mph, her sheer size heavily prolonged the intensity and duration that her concentric core raindbands dragged themselves over North Carolina’s hilly interior. Radar indicated rainfall intensities were very high within the storm’s circulation, quickly unleashing several inches of precipitation across wide swaths of the state.

As the storm progressed forward, it was not North Carolina’s Outer Banks that experienced the highest storm surge form the Hurricane. The highest values actually occurred north of the primary eyewall, along the Potomac and James Rivers. In Hampton, VA, a city north of Norfolk on the western side of the Chesapeake Bay (where the northern quadrant of Isabel’s circulation was pushing water directly onshore), a damaging storm surge up to 8.3 feet in depth was recorded flooding into the coastal portions of the town, urged forward by the wishes of ~20 foot waves. Other beaches along Chesapeake Bay’s tidal basin were inundated with seawater as deep as 11 feet, while multiple nearby locations regularly recorded wind gusts of 103-107 mph.

Storm surge was pushed up the Black River and into the Hampton Roads area, severely flooding Langley Air Force Base and the surrounding metropolitan geography. The Elizabeth River was forced backwards as well, resulting in an estimated 44 million gallons of the river’s water breaking through floodgates and flooding into the Midtown Tunnel. Elsewhere, waters rushing up the vast assemblage of the Potomac Basin’s tidal rivers caught many residents (who’d decided against evacuation, based on Isabel’s weakening up to landfall) off their guard. Many houses were severely damaged by ground-floor submersion; some were even wholly destroyed.

The worst damage, however, unfolded well inland, as the Hurricane’s highly-reflective rainbands poured down a bloodlust fury across the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia’s mountainous heart, with the same vigor and resentment that the clashing armies of the American Civil War had unleashed 140+ years before Isabel’s landfall. The storm’s center entered the state as a weakening, 75 mph Cat 1 core… but the convection embedded in her coattails remained as malevolent as ever. Widespread totals of 5+ inches sparked flash floods over a vast area of eastern Virginia, with a peak accumulation of 20.20 inches registered in Sherando. Trees collapsed and toppled, victims of a joint force of wind and saturated soil, and they killed many hapless victims with their fatal falls. The rainwater raced, channeled, conjoined, and clambered down steep valleys and ridges, funneling a vast expanse of tropical moisture into a concentrated mixture of mud and miscellaneous debris. The flooding was the regurgitated product of 12 days of frustration; for Isabel, it was her attempt to drown her distress away. She sank down in her tribulations, as her once-tantalizing, overpowering features decayed in the mortifyingly rapid progressions of old age and frictional degeneracy. As the darkening light at the end of the tunnel drew near, Isabel sobbed in the dissatisfaction of her exploits—after all the power she’d expended, all the beauty she’d poised with, and all the water she’d rained down on the U.S. East coast, a nagging malcontent of an immeasurable, indiscernible feeling of disappointment still clawed at her heart.

Exactly two weeks after Isabel’s birth—the storm whose slow, dreamy spin, forever emblazoned on the visual neurons of our minds—ended her life despairingly, in Ontario, Canada.

Isabel’s Inlet.

Hurricane Isabel was not the best, nor the worst, storm to ever impact the Mid-Atlantic states—but to this day, she stands as the costliest disaster in the recorded history of the state of Virginia. After the slow recession of both fresh and saltwater flooding, Isabel left a $1.85 billion dollar trail of destruction throughout the state, killing 10 while being indirectly blamed for the deaths of 22 others. In total, Hurricane Isabel was at least partially responsible for 51 human fatalities, all of whom were in the United States except for 1. Across New England, up to 6 million customers were without power at one point, and the job of restoring the energy would require the cleanup of thousands of downed trees and broken power lines. It would take several weeks for crews to fully reestablish the power infrastructure cut down by Isabel’s winds.

In the days after the storm’s passage, hundreds were left stranded on Hatteras Island, having no way to cross the newly cut Isabel Inlet. These residents were all eventually rescued, but in short order many people from the outside attempted to actually venture to Hatteras in hopes of seeing the already-famed canyon through the barrier island. It was as if the Isabel Inlet was now a regular tourist attraction for North Carolina’s Outer Banks (though that effect may have been ruffled a bit, with prospective viewers having to hike a mile distance from the nearest road amidst strewn piles of debris and filth).

Overall, the Hurricane caused $3.6 billion dollars of property losses. The following year, the World Meteorological Organization officially retired the name Isabel from the Atlantic naming list, citing the extensive destruction she inflicted on the U.S. East coast.

Isabel—that sweet, sweet name that rolls off the tongue with such an enchanting, seductive grace… only now, tainted with the dark bitterness of the lives she took, and the many creations of Humanity she needlessly wrecked. We’ll never know for certain if the essence of this great Hurricane endeavored to satisfy some vile, primitive impulse for violence she’d hidden in her heart from the beginning—of if her path was merely the chanced decision she was forced to make in the face of the obstinate Bermuda High.

But there is one thing that will always be for certain: when someone asks you, “What’s the most gorgeous storm you’ve ever witnessed as viewed from the soaring, orbital heights of space?”, simply show them the satellite records of Hurricane Isabel at the pinnacle of her blooming prime. And if that’s not enough to convince them of the power the Goddess of Hurricanes possessed during her life, then point them in the direction of Hatteras Island, North Carolina, and tell them to look for that painful gorge 2,000 feet wide and 15 feet deep…

Because rumor has it, you can still hear the windy whispers of the storm once named Isabel, softly calling “Goodbye,” through the trickling of water that passes down the inlet of her namesake.